Abstract: An interpretation is proposed for some glyphs depicting an obscure historical event in Tizoc’s reign, which can be found in Codex en Cruz 7, Codex Azcatitlan 19v. They refer to an Otomi rebellion at Chapa de Mota, consignated in Anales de Tlatelolco and Codex Huichapan f52

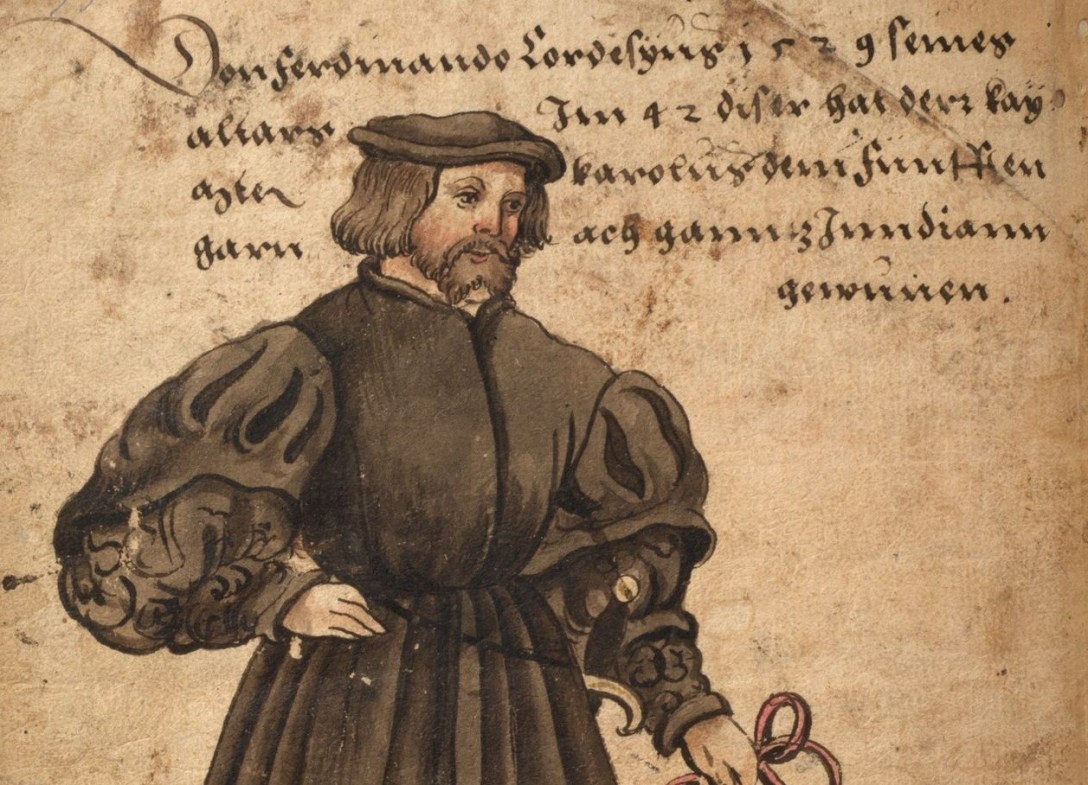

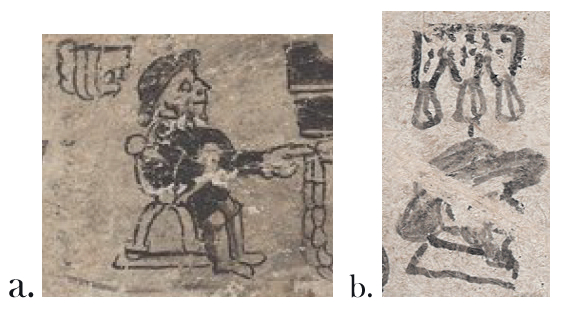

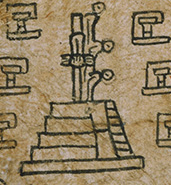

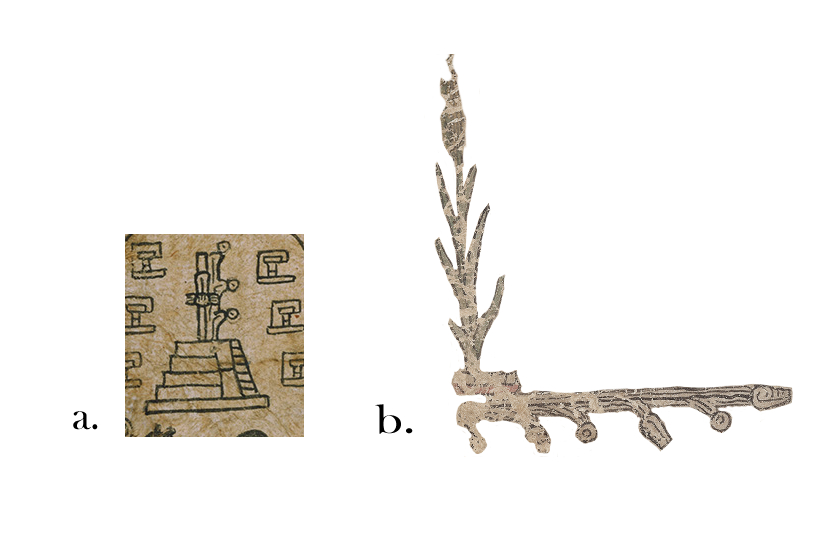

Since our knowledge of Aztec pictorials is relatively extensive, thanks in no small part to colonial glosses and the continued attention of modern scholars since the work of Aubin, not many people talk nowadays about any “mysteries” in Aztec writing, in contrast to the still important number of undeciphered signs in Maya writing, or the uncertainties surrounding Mixtec pictorials. However, the truth is that some “passages” in Aztec codices are indeed rather elusive. This entry is about one such obscure sections in a document that deserves more contemporary attention: I am referring to the Codex en Cruz, excellently edited and studied by Charles E. Dibble (1981). However, despite Dibble’s authoritative, accurate and (almost) exhaustive comment, there are still some parts of this document which are in the dark for our current knowledge. One of them is the upper section of the year 4 Reed (1483) in folio 7 in Dibble’s copy, G in the diagram that accompanies the original at the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris. This small bit of history, which happened during the reign of Tizoc, is only denoted by three mysterious signs: that of a snake above a disk of water, a wooden beam (huepantli), and a shield with a macuahuitl, which in this document usually denotes war (Figure 1).

Figure 1. a) The year 4 Reed (Codex en Cruz 7); b) The ‘water-snake’ and the ‘shield, macuahuitl and beam’ event in question, in the upper section. Both drawings are from Charles Dibble.

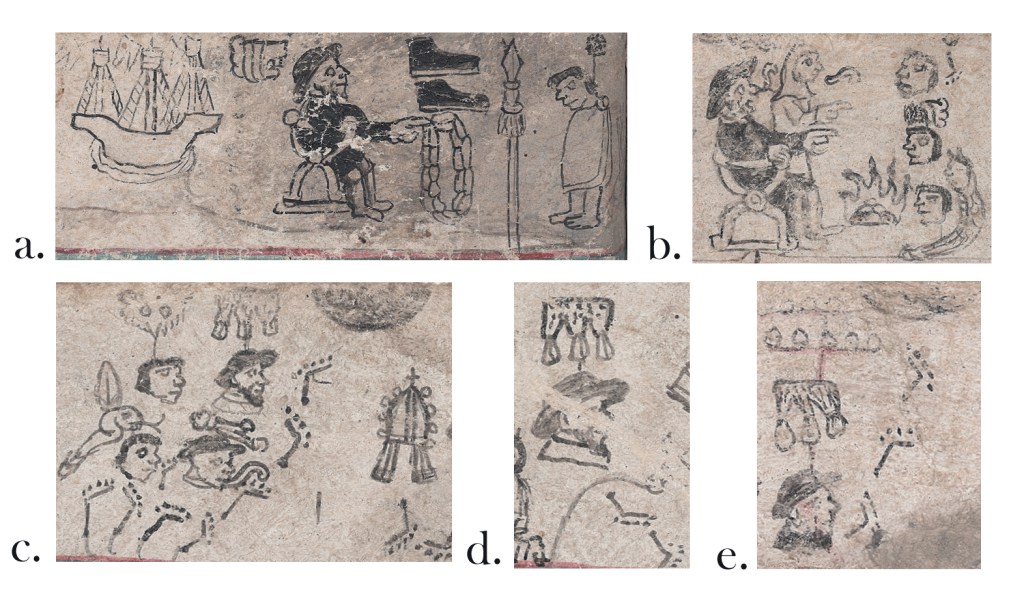

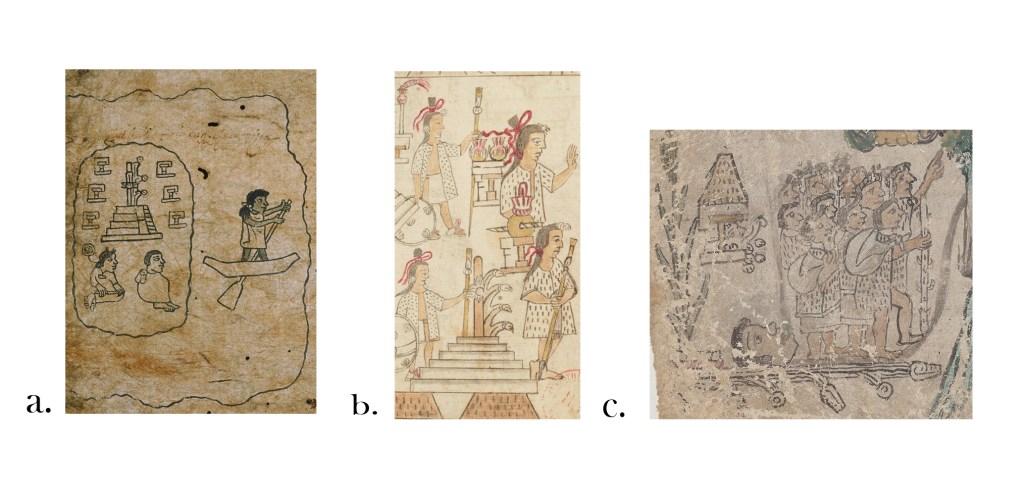

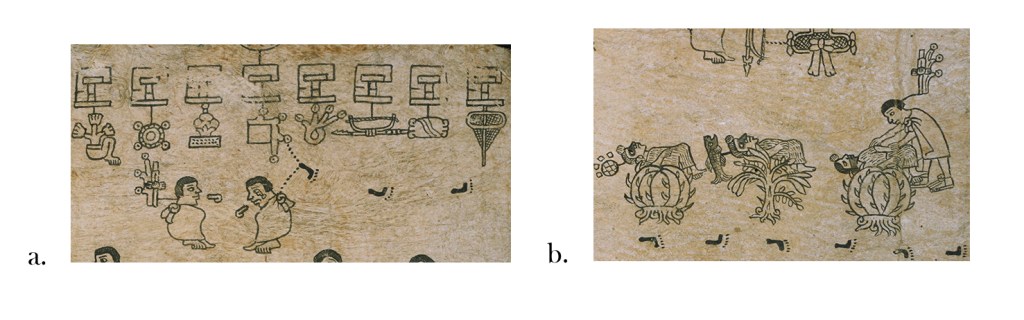

Before venturing a new reading of this passage, it is necessary to explain its context, and what Dibble has already said about it. The year 4 Reed or 1483 in the second 52 year cycle depicted in the Codex en Cruz corresponds to the reign of Ahuizotl, the short-lived seventh tlatoani of Tenochtitlan. Despite being a Tetzcocan manuscript, the history of Tenochtitlan, the seat of the power of the Culhua-Mexitin, is constantly present in it. The first sequence above the year sign has been interpreted by Dibble as the birth of a character named Huaxtzin in Chiauhtla; the second, to the raising of a temple at a location that may be very well Chiauhtla itself too (1981: 27). After this, another line divides the geographical scope of the events depicted in the column, and the glyph of Tenochtitlan situates the rest of the signs in relationship to this polity. Dibble (1981: 28)correctly interprets the event depicted directly above the Tenochtitlan sign as the laying of the foundation of the temple of Huitzilopochtli, one of the main events in Tizoc’s reign: we can see the king with his name-glyph, working with a digging stick above the foundation , an event depicted in most extant pictorial chronicles about his reign (like the Telleriano-Remensis and the Azcatitlan).

Afterwards, two captives are seen above the king, each associated to different glyphs. Dibble correctly observed that they were from Huexotzinco, thanks to the curved lip ornament that denotes the inhabitants of this Altepetl. He hypothesized that they were name-glyphs, but they are difficult to read: the first is interpreted by him to be an eagle, but the problem is that such predator could denote many names: Cuauhtzin and Tlotli are a couple of alternatives, among many others; the second, mostly effaced in the original, is even more obscure. A probable clue lies in Chimalpahin, which relates that in the year 4 Reed, not only the foundations of the temple of Huitzilopochtli were laid, but also captives from Cozcacuauhtenanco and Tlaollan were sacrificed (1998: 275). The first glyph could certainly resemble collar-less versions of the glyph COZCACUAUH, which are rare but do exist, or perhaps is a mere abbreviation of CUAUH. The second glyph, however, is almost impossible to figure out: it seems to be a face with a bun on its back, and therefore seems to have no relationship to the well-known toponym for Tlaollan, a basket with corn kernels, so this issue must be left unsolved for now, although I suspect that another close examination of the original could reveal something, since the different copies by León y Gama, Pichardo, and Dibble all disagree.

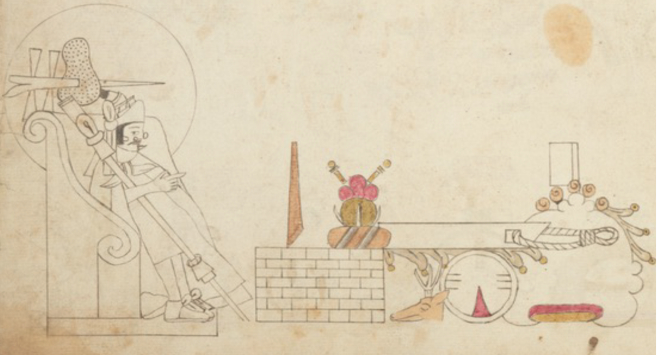

The names, or perhaps places of origin, of these captives are certainly an interesting question, but the mystery regarding what follows is the focus of this entry. Dibble, with a very insightful intuition, observed that an unknown toponym composed of a serpent with water, the shield and macuahuitl sign, and a beam (huepantli) sign, suggested a war-event related to the procurement of beams for the construction of Huitzilopochtli’s temple. He also relates these signs with a parallel and also obscure event depicted at Codex Azcatitlan 19v, which also happened during the reign of Tizoc: after the foundation-laying event in Tenochtitlan, denoted by a wall, a huictli (compare with Telleriano Remensis 38v), and the name-glyph of that polity, a very obscure compound of signs follows: the wooden beam sign with a cord, a shield, a deer’s head, and the name of an unknown place denoted by a body of water and a flag. Both passages remain obscure until now: Barlow suggested the reading Ahuepanco for the place by joining the water and beam signs. Recent re-examinations of the Azcatitlan, such as those by Graulich (1995: 120) and Rajagopalan (2019: 64), offer again Barlow’s tentative reading while remaining a bit skeptical.

Before offering a new interpretation/reading for this passage, something must be said about the main aspect of Aztec writing that is still obscure or undecided for us: what is the real nature of the signs that are neither toponyms nor calendric signs, nor numbers, nor names, which sometimes become completely difficult to differentiate from “writing proper” due to the iconic nature of the Aztec script, but definitely carry more information than their logosyllabic counterparts? For example, in this passage: what are the “shield and macuahuitl” sign which seem to denote the action of war rather than just the word yaotl, and the beam sign, which seems to denote more than the mere word huepantli, codifying a little story of sorts? Many labels have been offered for such signs: semasiography (Galarza 1990, Boone 2000), iconography (Lacadena 2008) or, a proposal that has great potential, that of “embedded texts” of Janet Berlo (1983), which Albert Davletshin (2003: 62) and Dmitri Beliaev (2016: 205) have urged us to re-consider. However, it is more prudent to “suspend judgment” on this question for now, but it is important to keep it in mind, because it can give us an inkling on what Aztec writing itself was about.

The truth is that the method of interpretation followed by Dibble was very insightful and pertinent, and, as we will see, it retains its relevance. Roughly speaking, it consisted in assessing the glyph’s iconography and consider possible readings, and then offering an explanation for their apparition through parallel events in alphabetic chronicles and other pictorials in order to substantiate the interpretation. After searching for possible parallels, I feel that it is possible to propose a reading for this passage, which was obtained by following a similar method to that of Dibble, although aided by the enormous advances in the catalogation and understanding of Aztec script brought by later specialists (Thouvenot 2012; Zender et. al. 2013). As mentioned, the idea was simple: to look for passages of historical events associated to Tizoc which can be related to these glyphs regarding of what they looked like, and see if anything could fit. The relevant passage is in a source that Dibble actually used in his edition of the Codex en Cruz: Anales de Tlatelolco. There we read the following concerning the year 5 Flint (1484):

Quiualtzaque in chiapantlaca, uepanato Itzmiquilpa, ahuehuetl in quiuillanato ytlaquetzallo yezquia yteucal Huitzilopochtli; y no umotlatziuhcaneque contlatique yn iuepamecauh y quiualtzaque.

The Chiapantlaca rebelled, they were cutting ahuehuetes in Iztmiquilpan, which they dragged to make the columns of the temple of Huitzilopochtli: they rebelled when they worked with laziness and burned the cords which they used to drag the logs (Tena 2004: 96-97).

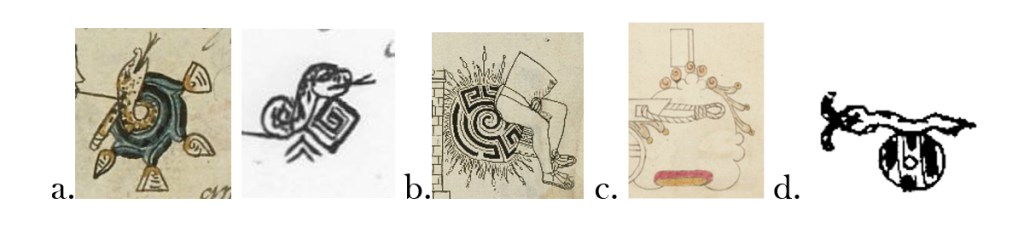

Thus, we have a passage clearly related to the context that Dibble (correctly) guessed: a rebellion or war event related to the beams used to start building the temple of Huitzilopochtli, which happened during the reign of Tizoc. The only difference is the date, which in the Tlatelolco chronicles is set one year later, but the rest of it is identical: furthermore, the Tlatelolco document set the accession date of Tizoc 1 year later than the Codex en Cruz, at 3 Rabbit, but the discrepancy is easily explained through the disparity of local historiographic traditions. But what about the glyphs? The ‘snake and water’ sign is clearly the toponym of Chiapan/Chiyauhpan. It is related to the root chiyauh, ‘filth, grease’; Molina also reports that chiyahuitl was a certain kind of snake (Wimmer 2004a), probably living in swamps. It seems that this root was either depicted by a marsh, by the snake, or by both, to form the logogram CHIYAUH, ‘filth, grease, swamp snake’. The CHIYAUH logogram appears in the Matricula de Huexotzinco to denote the name chiyauhcoatl, or ‘marsh snake’, and the toponym chiyauhtzinco, “place of the little marsh”, for Chiyauhtlalli means swamp or marsh, just as the name sign depicts.[1] Thus, the snake and water sign is a somewhat abbreviated form of the toponym Chiyauhpan, or Chiapan, “place of marshes”. This can be better understood by comparing with the renditon in the Azcatitlan, which has the marsh sign next to a flag or pa syllabogram, forming CHIYAUH-pa, Chiyauhpan.

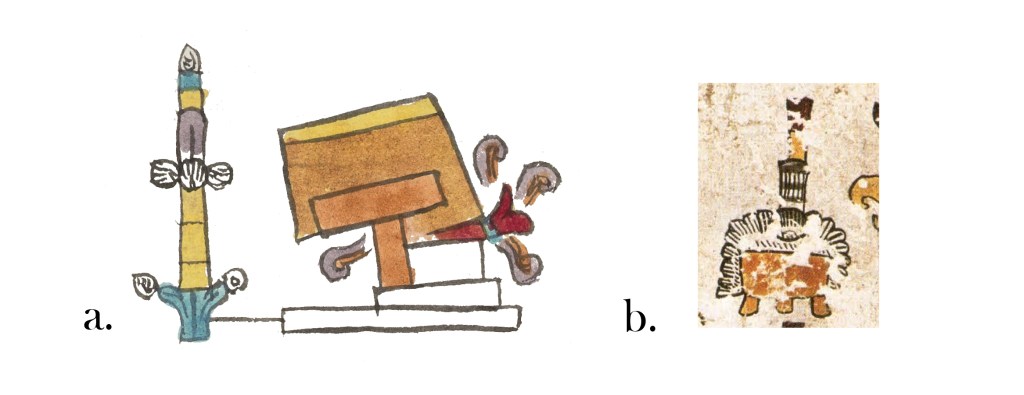

The rest is, of course, easy to understand in the Codex en Cruz through the parallel alphabetic passage in the Anales de Tlatelolco, but not so in the Azcatitlan. In the Codex en Cruz, the ‘shield and macuahuitl’ sign is a ‘pictogram’ for war/rebellion, as it is in the rest of the Codex, while the beam or huepantli sign explains the circumstances of this war: hence, the final reading would have been similar to that offered in the Anales de Tlatelolco. But what about the Azcatitlan? Here something interesting happens. The toponym Chiyauhpan is clearly read CHIYAUH-pa: the tepetl or ‘mountain’ sign is, again, ‘iconographic’, ‘semasiographic’ or whatever terminology we want to use, only denoting the abstract idea of an Altepetl polity, the place where the action occurred. But what about the water sign, which gives an unlikely complement to huepantli? It is probable that this sign simply is a spelling added to indicate something like ahuehuepantli, that is, ‘beams made of the ahuehuetl tree’. Another explanation, offered to me by Gabriel Kruell, is that the sign actually denotes the verb huepana, “to drag wood”, a solution that is also likely. The shield sign is another variant for the aforementioned pictograph of war, and is identical to the version present at the Codex Aubin; however, its motivation is also related to how the war actually started, according to Otomí sources.

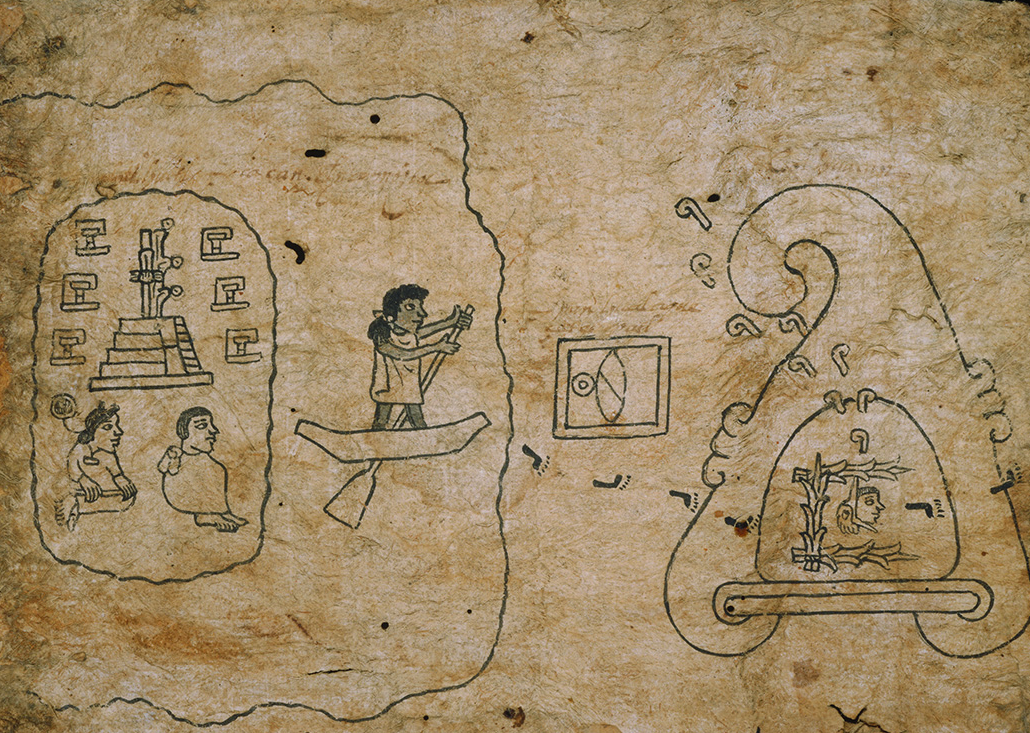

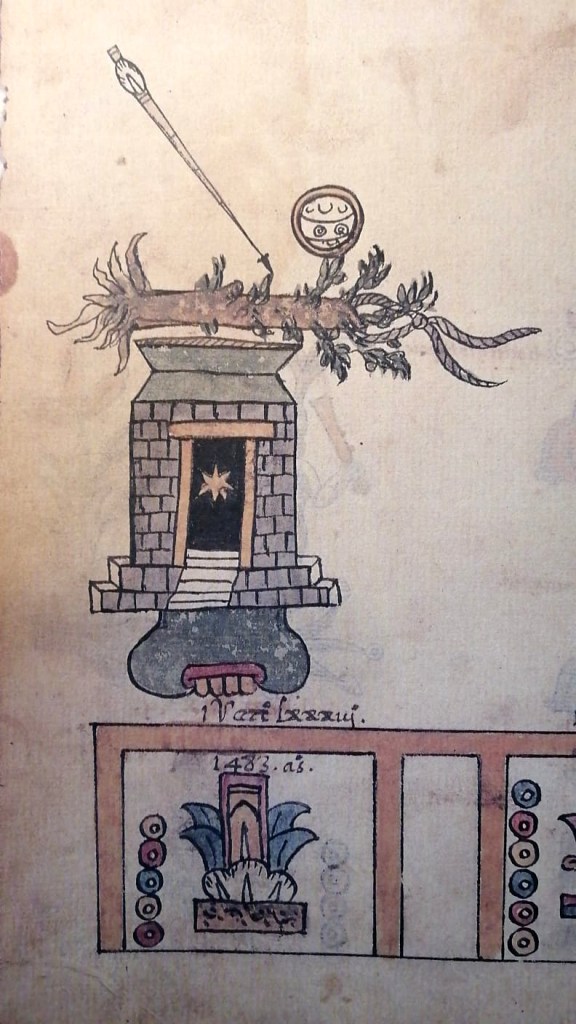

Indeed, the final confirmation for this reading, as well as the full details of this event from the point of view of the rebels, comes from Codex Huichapan, an Otomi codex. In the folio 52 of this document, the same event is represented, associated with the year 5 Reed of the Otomi calendar (Figure 4). The Otomi gloss gives us an insight on the actual location of this rebellion, and the true reasons for it: in fact, the rebellion started because the Aztec wanted the Otomi to drag a huge ahuehuete tree; however, the Huichapan Codex states that the tree would not budge after reaching Tlalnepantla: hence, they left a shield above the tree, and the rebellion started:

Quequa pintu mabagui anyänttoho queemuuti quütuy nucca ntza anqhuuttatzâ nucca hinpinettzi pahênibatho antzunmahoy chanubuu mambähenbi nucca ntza pahoxtho nucca mbuobây piyotho nucca mabagui nucco mënyänttoho cancatuy nuhna mabâgui nubayänttoho.

Here began the war in Chapa de Mota: it started with the rooted tree that could not be lifted, it only reached to Tlanepantla amid the lands, and when they came to take the tree further, they just laid a shield on it. The war with those of Chapa de Mota was re-started: thus began the war at Chapa de Mota. (Ecker 2003: 79).

Finally, only the deer head remains mysterious. There are two possibilities. The first, considered by Barlow, is that it represents Tizoc’s conquest of Mazatlan (1949: 125), but the problem is that conquests in the Azcatitlan usually have the tepetl or ‘mountain’ sign denoting a polity or altepetl. Herren Rajagopalan’s recent study on the Boturini, Aubin and Azcatitlan offers an explanation which solves this problem in my point of view. This deer head is clearly incomplete, lacking the bottom part of its ‘frame line’: Rajagoplan suggests that it is an incomplete day-sign, and I agree that this is the most likely explanation in graphic terms (2018: 64). Probably, it states the day where the rebellion occurred. With all these elements, the passage is finally clear.

All things considered, this little bit of history doesn’t seem like much. But this exercise in interpretation tells us something important: the logic of Aztec tlacuillolli as a full communication system was overwhelmingly pictorial, and in it sometimes it can be actually difficult to ascertain the separation between ‘writing’ and ‘iconography’. We are left in the dark about the meaning of the whole when we consider the individual signs in isolation, to the point where we don’t really know if they are ‘iconography’ or ‘writing proper’: we need a historical context, transmitted to us through alphabetic glosses, to get a grasp of the nature of the signs and the ‘embedded text’ contained in them. This ‘embedded text’ probably roughly corresponded to the alphabetic account of the Anales de Tlatelolco, rather than to a text only produced by the reading of these signs as logograms. Of course, these assertions are conflictive with the current narrow definition of writing (Daniels 1996: 3), which specifically states that any system that needs the intervention of the original utterer (here, the tlacuilos ‘speaking’ through the alphabetic colonial versions of Aztec histories) to relay its full message is not writing, for writing is not considered as a mere assembly of signs but as the whole working of them. The dilemma is this: can tlacuilolli, taken as a whole rather than at the level of names, be considered as writing, or we need to continue using the split ‘iconography’ vs writing which doesn’t really correspond to the native categories, who lacked a word to distinguish logograms/syllabograms from “iconography”?

Regardless of the solution to this conundrum, which I cannot advance here, it must be said that the logic of these documents is dominantly ‘top-down’ rather than ‘bottom-up’: unlike in Maya writing, we gain little by the correct understanding of individual signs (as Barlow’s mistake makes evident), while contextual meaning is everything. It is also not always clear when something is “iconography” merely because of its appearance: the ‘war’ sign and even the beam sign, which denote something beyond mere names, or even more, can effectively double as “names” and “embedded texts”, proves it. In any case, the heuristics introduced by Dibble for this document still hold up, and can be used to our advantage in other obscure passages in Aztec writing: ‘attack’ the context as far as reliable parallel alphabetic sources permit it, and the signs will fall in place themselves; only after these possibilities are exhausted we can venture hypotheses based on analogies to known “pictographic” and logosyllabic signs. Of course, as mentioned, originally the source of this full reading was nothing else but that which Daniels calls ‘the original utterer’, that agent which in the perspective of current mainstream grammatology forbids Aztec writing from being considered ‘real writing’: a tlacuilo, a trained painter-writer in the historical tradition, which closed the gap between these signs and the reader and uttered for the readers a full message. But the answer to this question must be left for the future.

Acknowledgements

I want to thank Stan Declercq for facilitating me the relevant pages of Graulich’s edition of the Codex Azcatitlan. As in many other entries, I also want to thank Gabriel Kruell for reading this text and offering his views on it. He offers the following reading for the Azcatitlan: “Tizocicatzin was installed on the throne. In this year, he laid tezontle on the Temple of Huitzilopochtli. The inhabitants of Chiapan rebelled, wooden beams were brought from Itzmiquilpan, ahuehuete logs were dragged to serve as beams in the temple of Huitzilopochtli, but they didn’t want to work, they burned the ropes, and they mutinied”

References

Anonymous. 2004. Anales de Tlatelolco. Trans. Rafael Tena. Mexico: CONACULTA

Barlow, Robert. 1949. “El Códice Azcatitlán.” Journal de la Société des Américanistes 38: 101-135.

Beliaev, Dmitri. 2013. “Genesis of History Writing in Ancient Mesoamerica » in Dimitri Beliaev, and Timofey Guimon, eds. The Earliest States of Eastern Europe, 203-241. Moscow: Dmitriy Pozharskiy University.

Hill-Boone, Elizabeth. 2000. Stories in Red and Black. Pictorial Histories of the Aztecs and Mixtecs. Austin, TX: University of Austin Press.

Berlo, Janet. 1983. “Conceptual categories for the study of text and image in Mesoamerica”, in Janet Berlo, ed. Text and image in Pre-Columbian art. Essays on the interrelationship of the verbal and visual arts. Proceedings, 44th International Congress of Americanists, 79-118. Manchester, Oxford: BAR Publishing.

Chimalpahin, Domingo. 1998. Las ocho relaciones y el Memorial de Colhuacan. Trans. Rafael Tena. Mexico: CONACULTA.

Daniels, Peter T. 2006. “The Study of Writing Systems”. In Peter T. Daniels and William Bright, eds. The World’s Writing Systems, New York & Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 3-18.

Davletshin, Albert. 2003. Paleography of the Ancient Maya Hieroglyphic Writing, Ph.D. diss., Moscow: Russian State University for the Humanities, Knorozov Center of Mesoamerican Studies.

Dibble, Charles. 1981. Codex en Cruz. Salt Lake City, UT: University of Utah Press.

Ecker, Lawrence. 2004. Códice de Huichapan: Paleografía y traducción. Eds. Yolanda Lastra and Doris Bartholomew. México: UNAM.

Galarza, Joaquín. 1990. Amatl, Amoxtli. El papel, el libro. Los códices mesoamericanos. Guía para la introducción al estudio del material pictórico indígena. México: Tava.

Karttunen, Frances. 1983. An Analytical Dictionary of Nahuatl. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press.

Lacadena, Alfonso. 2008. “Regional Scribal Traditions. Methodological Implications for the Decipherment of Nahuatl Writing.” The PARI Journal 8 (4): 1-22.

Rajagopalan, Angela Herren. 2019. Portraying the Aztec Past: The Codices Boturini, Azcatitlan, and Aubin. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press.

Tena, Rafael. 2004. Anales de Tlatelolco. México: Conaculta.

Thouvenot, Marc (2012). Tlachia [online]. National Autonomous University of Mexico <https://tlachia.iib.unam.mx/>

Wimmer, Alexis. 2004a. “Chiahuitl.” In Dictionnaire de nahuatl classique. https://gdn.iib.unam.mx/diccionario/chiahuitl/43696 (accessed 17 May 2021).

Wimmer, Alexis. 2004b. “ Chiyauhtlalli.” In Dictionnaire de nahuatl classique. https://gdn.iib.unam.mx/diccionario/chiyauhtlalli (accessed 17 May 2021).

Zender, Marc, Davletshin, Albert, Lacadena, Alfonso, Stuart, David, and Wichmann, Søren. 2013. An Introduction to Nahuatl Hieroglyphic Writing. 2013 Maya Meetings and Workshops, University of Texas, Austin. Austin, TX: University of Texas at Austin.

[1] Chiyahu(a): ‘To get something greasy’. Chiyahuac: ‘Something greasy, grimy, filthy’ (Karttunen 1983: 54). Chiyauhtlalli: Pantano (Wimmer 2004b).