Abstract: A proposal for the glyph NAHUAL, nahual·li, ‘hidden, covering, sorcerer’ glyph in Aztec writing is presented here, as well as an overview of the (unsolved) debate on the root nahual. In the opinion of the author, the iconography of the nahual glyph, as well as its semantic connotations, seems to lend support to the opinion of Katarzyna Mikulska (2011) and of Roberto Martínez González (2016), who proposed that this root was related to covering and disguise, rather than to speech or incantation.

“Nahualli: A sorcerer; a shape-changer; a spirit, often an animal form or shape a person could take.”

Online Nahuatl Dictionary

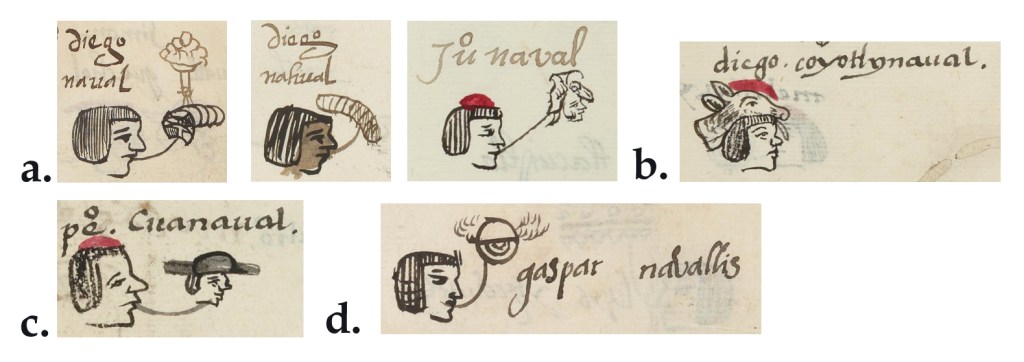

Unlike its more famous Maya counterpart, WAY, way, ‘co-essence, sorcerer, to sleep’, the glyph denoting the rather polemical root nahual, ‘hidden, covering, sorcerer’ in Aztec writing has been largely ignored in scholarship. Perhaps this obeys to the fact that the way glyph, first identified by Stephen Houston and David Stuart in a now classic article (1989), is of a tremendous importance in Classic Maya writing and particularly in ceramics, being attested in well-known masterpieces as the famous vase of Altar de Sacrificios (K3120); in contrast, the nahual glyph (which later I will show to be related to the notion of sorcery too) appears in very limited occasions in Aztec writing, and its iconography is rather distant from the spectacular half-man, half-jaguar face that denotes its Maya equivalent. Instead, the nahual glyph (Thouvenot 2012) is really humble, almost disappointing in form: it mostly consists in a human face under a number of coverings (hats, animal heads), or, even more comically, of what seems to be a worm hiding inside a turtle shell, or even a half-darkened worm (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Different instances of the NAHUAL, Nahual, ‘hidden, covered’ glyph in the Matrícula de Huexotzingo a) NAHUAL, Nahual, ‘hidden, covering’: notice the ‘worm inside turtle-shell’ variant, the ‘half-darkened worm’ (hiding in shadows or underground) variant, and the ‘head inside snake’ variant (497r, 309r, 872v) b) COYO-NAHUAL, Coyo(tli)nahual, ‘a coyote is his covering’ (667r); c) CUA-NAHUAL, Cuanahual, ‘head covering’ (673v); c) NAHUAL-IX, Nahuallix, ‘covered eye’, probably refering to the eyelid and the eyebrow (?) depicted (488r).

Despite its lack of charm, the nahual glyph is interesting, because it could serve to bring more arguments to the (rather difficult) debate on what is exactly the origin of this root in Nahuatl and its relationship with the word nahualli, ‘sorcerer’. Many hypotheses have been proposed, but all of them derive (or distance themselves) from Juan Ruiz de Alarcon’s opinion, presented in his treatise on Aztec sorcery (1629): “The name and meaning of the noun nahualli can be derived from one of three roots: the first meaning ‘to command’; the second “to speak with authority”, the third, “to hide oneself” or “to wrap oneself up in a cloak”. And although there are conveniences for which the first two meanings apply, the third suits me better since it is from the verb nahualtia, which is “to hide oneself by convering up in a cloak”, and thus nahualli probably means “a person wrapped up or disguised under the appearance of such an animal”, as they commonly believe” (Ruiz de Alarcón 1987: 48).

Before reviewing the modern debate on this reconstruction, it must be clarified that, in Nahuatl, there are two very similar roots that are behind this problem: nahua, which means ‘to be audible, intelligible, clear’ (Karttunen 1992: 157), as well as ‘to embrace’, and a root nahual, which means means “to transform, convert, transfigure, disguise, re-clothe, mask oneself, conceal, camouflage, and finally to trick” (Mikulska 2010: 327), which is verbalized as nahualtia. However, as we will see, the problem is that there is no real agreement not only on the actual meaning of the root nahual, but also on whether it is a real root, or whether it actually derives from a form of nahua, and if so, in which sense.

The problem is very complex. For example, Frances Karttunen, following colonial dictionaries, lists the root nahual as meaning ‘sorcerer’, and derives the latter from an extended meaning of the root nahua, ‘to be audible, to speak’: “The basic sense appears to be ‘audible, intelligible, clear’, from which different derivations extend to ‘within earshot, near’, ‘incantation’ (hence many things to do with spells and sorcery) and ‘language” (2016: 157). This would be (mutatis mutandis) an example of agreement with Alarcon’s first two hypotheses, and is a very reasonable position, based on what we know of post-conquest Nahuatl.

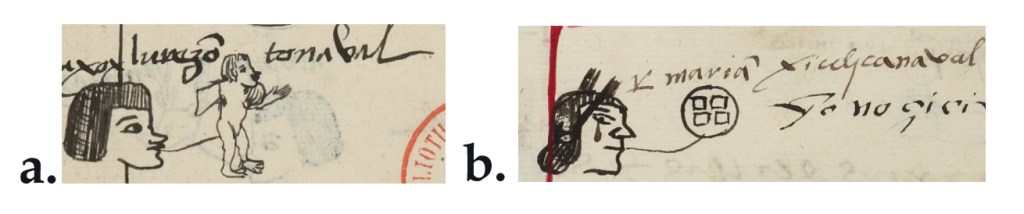

As mentioned, in her article on the idea of ‘secret language’ (nahuallatolli) in Nahuatl culture, Katarzyna Mikulska proposed that the root nahual is actually related to the idea of disguise, covering, concealing, and tricking, rather than only to sorcery, as the colonial dictionaries imply (2010: 327). Similar to her opinion, but a bit different, is the proposal of Roberto Martínez González in his work El nahualismo (2016), perhaps the most important on the topic. Essentially, Martínez González discards the derivations from nahua, ‘to speak, to command’, and nahualtia, ‘to disguise, to cover’, since “the nāhualtia form can be derived from the substantive nāua-l-li, whose sense we seek to understand, plus the transitivizer suffix –tia.” (2016: 82). He equally discards the root nāhua, ‘to embrace, to dance’, because of its lack of correspondence with the sorcerous connotations of nahualli; another explanation whom he rejects is that of Alfredo López Austin (1967: 96), who associates the root ehua, skin, with a first-person possessive n-, proposing the etymology “that which is my covering”. Martínez González considers that the word has little to do with ehua, but considers that the nahua root is indeed associated with the idea of contour, covering or disguise, based on evidence such as the contemporary Tlaxcallan Nahuatl word nahual, ‘coat’ (gabán). Indeed, it seems that all of these meanings (‘to embrace, contour’) associated with a nahua root are not absent from Aztec writing, since they are all iconographically attested (Figure 2), making things a bit more complicated.

Figure 2. Possible instances of nahua as ’embrace’ and ‘surround’ in the Matrícula de Huexotzinco a) NAHUA, (To)nahua(l) (704r) b) XIUH-NAHUA, Xiuh(ca)nahua(l) (795v).

After pondering (and discarding) other proposals, like that of Ángel María Garibay, Martínez González settles on a hypothetical primitive nāhua root that would be related to the idea of disguise: “In summary, we can say that, although the exact derivation of the term nahualli is still unsolved, its general sense has been elucidated: it is akin to the notions of ‘disguise’ and ‘covering’.” (Martínez González 2016: 88). There are considerable difficulties in the reconstruction of this speculative nahua root; hence, in this article I have adopted something closer to Mikulska’s position, which is synchronic, and simply state that in Nahuatl writing there is a glyph NAHUAL, nahual·li, ‘hidden, covering, sorcerer’.

Now, the reader may wonder: what does the former examples have to do with Aztec sorcerers? After all, the colonial names attested here obviously do not denote names related to sorcery, but to the meaning of ‘hidden, covering’, as well particular types of headdresses. Of course, these examples clearly lend weight to the hypothesis that the nahual root is actually being related to the idea of covering and disguise, as Mikulska and Martínez González inferred, rather than just to the idea of sorcery, which is what we find in colonial dictionaries. In support to incorporating the meaning ‘sorcerer’ to this glyph, I would like to add a (particularly beautiful) final example which may portray an actual nahualli sorcerer or ‘man-god’ in the sense of Alfredo López Austin (1973) or the “nahualli-man” as studied by Martínez González. This example is to be found at the Historia Tolteca-Chichimeca, where it records the title of one of the ten tlatoque or rulers of Cholollan, one being the nahualle tlamacazqui or “sorcerer-priest”, a ruler of the Olmeca-Xicallanca, who were famed because of their sorcerous powers. This graphic realization (a rather grim soot-covered priest inside a cave) conflates the sense of the root as ‘cover, disguise, hiding’, since the since the character is seen to be hidden inside a cave, and the idea of the nahualli as a powerful ritual specialist, a ‘man-god’ of sorts (Figure 3). While this is far from conclusive, this glyph seems to confirm Mikulska’s and Martínez González intuition: that the root nahual has to do with disguises and coverings, and that it was extended to the sorcerers known as nahualli, which were ritual specialists that used their co-essences as a ‘disguise’ of their true selves in their workings of offensive sorcery. Hence, following both Mikulska’s proposal and considering Karttunen’s entry for nahual, I would propose the NAHUAL, nahual·li, ‘hidden, covering, sorcerer’ glyph as a counterpart of the now famous Maya WAY, way, ‘co-essence, sorcerer, to sleep’ glyph, its graphic realization being many sorts of iconographic strategies denoting the idea of being hidden, or covered.

Figure 3. NAHUAL-TLAMACAZ, nahual(li) tlamacaz(qui), ‘sorcerer priest’ (Historia Tolteca-Chichimeca 10v).

Acknowledgements

I want to thank Gabriel Kruell for his comments on this entry.

References

Houston, Stephen, and David Stuart. 1989. The Way Glyph: Evidence for “Co-essences” among the Classic Maya. Research Reports on Ancient Maya Writing 30, Washington DC: Center for Maya Research.

Karttunen, Frances. 1983. An Analytical Dictionary of Nahuatl. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press.

López Austin, Alfredo. 1967. “Cuarenta clases de magos en el mundo náhuatl.” Estudios de Cultura Náhuatl 8: 87-117.

López Austin, Alfredo. 1973. Hombre-Dios. Religión y política en el mundo náhuatl. México: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Instituto de Investigaciones Históricas

Martínez González, Roberto. 2016. El nahualismo. México: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Instituto de Investigaciones Antropológicas.

Mikulska Dabrowska, Katarzyna. 2010. “‘Secret Language’ in Oral and Graphic Form: Religious-Magic Discourse in Actec Speeches and Manuscripts.” Oral Tradition 25(3): 325–363,

Ruiz de Alarcón, Hernando. (1629) 1987. Treatise on the Heathen Superstitions that today live among the Indians Natives in this New Spain. Eds. Richard Andrews and Ross Hassig. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press.

Thouvenot, Marc (2012). Tlachia [online]. National Autonomous University of Mexico <https://tlachia.iib.unam.mx/>