Abstract: In this entry, I argue that Hernán Cortés had two glyphs denoting him in Nahuatl writing, both appearing in Codex Mexicanus: a) te, (Cort)és, Cortés, this glyph denotes his name; b) ez, (marqu)és, Marquess; this glyph denotes Cortés nobiliary title, and derives from the glyph EZ, eztli, 'blood', perhaps working in a syllabic way.

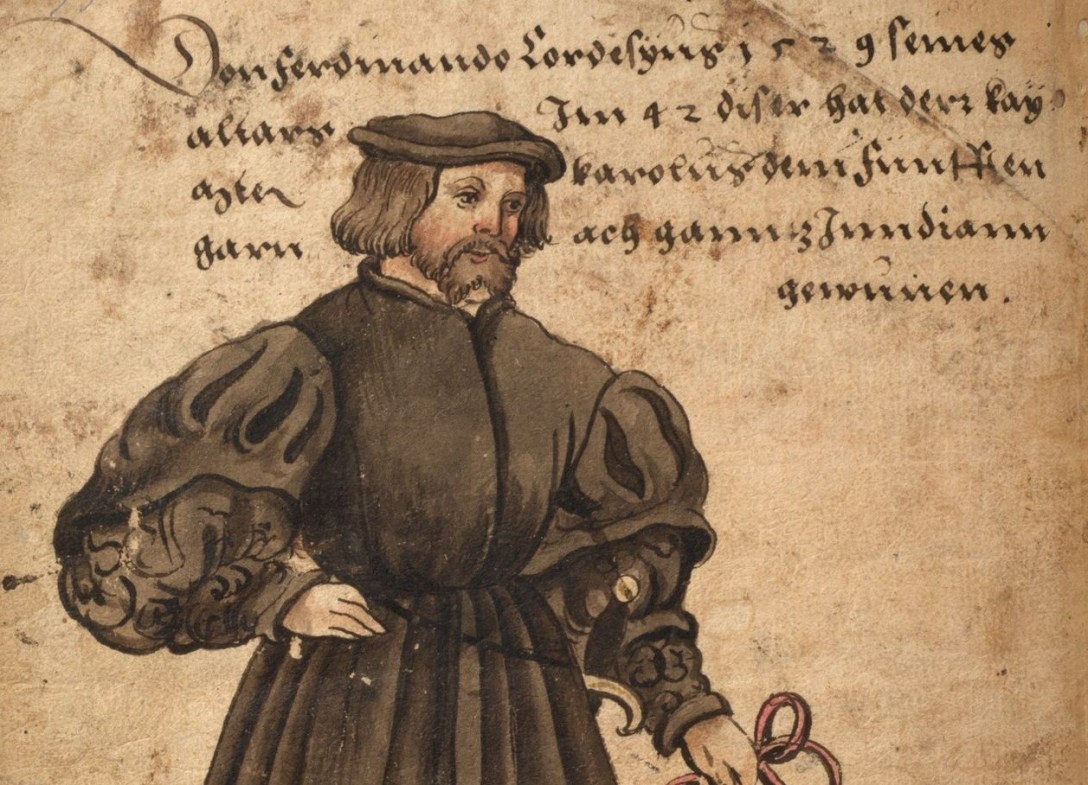

Despite his historical importance and being a familiar presence in Aztec colonial pictorials, the name of Hernán Cortés is a rare sight in Nahuatl writing. The conquistador is usually depicted with his name, or the title marqués, in alphabetic characters; iconographically, he is easy to recognize by the severe black garments that were de rigeur for any aspiring nobleman in the nascent Spanish empire, specially one of a dubious social standing, as he was. His iconography across many pictorials is quite consistent: completely black-clad, a feathered hat, and sitting on a Savonarola style Renaissance armchair (Figure 1).

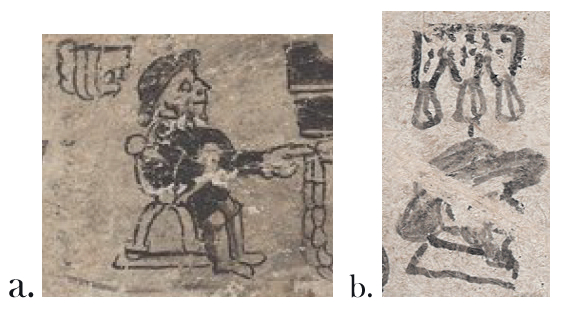

Most Aztec colonial pictorials coincide in representing Cortés as nameless in terms of Nahuatl glyphs, not even depicting his title. The glyphic names of other Spanish conquistadors and imperials are better known, to the point of being nowadays textbook examples of Nahuatl strategies on the hieroglyphic representation of European names: Pedro Alvarado, called Tonatiuh by the Aztec, has a sun glyph as his name, read as TONA, Tona(tiuh), in Codex Telleriano Remensis 46r; another famous example is vicerroy Mendoza, rendered as me-TOZA, Me(n)doza. Similarly, Spanish titles are rather common in colonial Aztec writing: vicerroy, ix-e-EL, probably ix-le-e, (v)is(o)rrey; doctor, to-TOL, dotor; executor or factor: e-pa-TOL, e(l) fa(c)tor (cfr. Valle 2006). But what about Cortés, and his title, Marquess of the Valley of Oaxaca? Recently, a new edition of Codex Mexicanus, by María Castañeda de la Paz and Michel Oudijk (2019), has appeared. This late-style document still keeps many secrets for those passionate about Aztec writing. Among its oddities, this document clearly depicts Cortés with a name glyph in many, although not all, of his appearances: his meeting at San Juan de Ulúa (actually San Juan de Culhua, as Robert Barlow remarked, 1990: 218) with the Tlillancalqui, one of the great constables of Tenochtitlan, his travel to Spain in 1527 and his return in 1530, and his final departure from New Spain in 1540, never to return (Figure 2).

Let’s concentrate on the couple of glyphs that denotes Cortés, which are not without their particular problems; first, that which denotes his fated meeting with Moctezuma’s envoys (Figure 3). Mengin suggested it was the nameplace of Tecpan Tlayacac (1952: 463), but it doesn’t resembles the appearance of this toponym in Tepetlaoztoc 4b, and we know the meeting was instead in San Juan de Ulúa; Boornazian Diel suggests a resemblance to the glyph of Tecamachalco in Codex Mendoza 42r, and a phonetical assimilation from CAMA-te to Cortés (2018: 141). Finally, Castañeda de la Paz and Oudijk considered that the name is indeed Cortés’ name, rather than a toponym, but offer no solution to its reading. It seems that the solution is perhaps anticlicmatic; the name probably reads: te, (Cor)te(s), Cortés, presenting the tentli+tetl variant of the syllabogram te. Regarding the first possibility, this kind of extreme abbreviation was not unknown in Nahuatl writing: another amusing example is that of Cepatzac, abbreviated to ce in the Matricula de Huexotzinco 387_838v. Before moving on, another thing must be added on the envoy of Moctezuma depicted here. It has been suspected that this glyph denotes the envoy that Bernal and Cortés called Tendile (sic), or Tentlil in Nahuatl according to Sahagún (Castañeda de la Paz and Oudijk 2019: 171), but given the gloss in the Durán Codex that calls the same character Tlillancalqui (see Figure 1), I consider it more probably that the tlilli, ‘black ink, soot’ glyph denotes the title rather than the name.

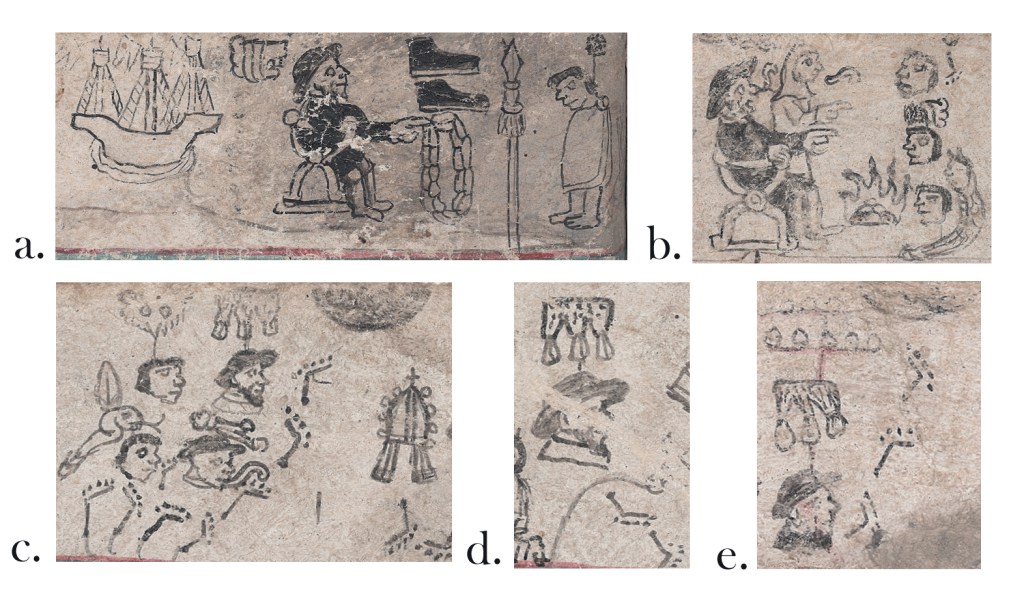

More complicated, in both an iconographic and epigraphic perspective, is the couple of scenes depicted at page 78. Commentators on the Mexicanus have long known that these scenes depict Cortés’ travel to Spain in 1528 alongside Aztec noblemen and lords, and his return in 1530 (cfr. Mengin 1952: 471-474; Castañeda de la Paz and Oudijk 2019: 177; Diel 2018: 148). Cortés has here another name sign that denotes him: dubbed trois gouttes d’eau qui tombent by Mengin (1952: 473) and ‘rain’ by Diel (2018: 147), the sign is rather close iconographically to the glyph QUIYAUH, quiyauh, ‘rainstorm’. A reading for glyph has been elusive. Mengin was doubtful between attributing it to Cortés or considering it a ‘viceregal’ glyph of sorts (1952: 473). Diel proposes that, somehow, QUIYAUH could have been assimilated to the Spanish marqués, but she doesn’t offers an explanation for this assimilation, although I believe her identification to be correct (2018: 143). María Castañeda de la Paz and Michel Oudijk concede they have no possibilities in mind for its reading (2019: 177). On close examination, the answer seems to lie in an aspect of Nahuatl writing that is unevenly depicted in Codex Mexicanus: colour. Thus, while this glyph is certainly iconographically certain to QUIYAUH, it is not actually it. Instead, this glyph closely resembles that at Mendoza 65r, which appears in the spelling of the title Ezhuahuacatl, one of the great constables of the Aztec empire (Figure 4)

The Ezhuahuacatl glyph is rather intriguing. It is clearly depicts a ‘blood-sign’ iconography, being a red liquid with green jade dots, for blood was a precious liquid. But what about the stripped pattern? A colleague, Gabriel Kruell, suggested me that this pattern could be an allusion to huahuana, “to scratch, scrape, to incise lines”. Hence: EZ-hua, ezhua(huacatl), Ezhuahuacatl. And Cortés? Cortés could be a case where EZ is working here perhaps in a syllabic way, as ez, deviating a bit from its standard reading. Anomalous, but given the still obscure processes by which foreign names were rendered into Aztec writing, it is not improbable. In any case, the real question is the following: is this glyph the name Cortés, or marqués, his title? Technically, it is impossible to know, but what is certain is that the ez glyph reappears associated to Hernan’s Mestizo son, Martín, in the following pages (Figure 5).

Indeed, the ez glyph reappears multiple times in the latter portions of the Mexicanus, this time associated with the events of Martin’s life. It appears at his arrival with the visitador Jerónimo de Valderrama (another epigraphic nightmare) in 1563, at the execution of the Dávila brothers, his supporters, in 1566, and at his exile in 1567. The glyph is undoubtly his, but the problem is that Martín Cortés was both a Cortés and a marquess, like his father was. However, my hunch is that Diel was right, and despite this lack of certainty, the ‘blood’ glyph ez is actually marqués, because the glyph for Cortés already appeared before, and this name glyph changes just after Cortés started styling himself after a nobility title which was specially favoured to denote him in retrospective indigenous chronicles like Codex Aubin, where nothing is said about the arrival of Cortés nor of his exploits, but rather about those of the marqués (cfr. Tena: 2017: 55ff.). In any case, this ominous ‘blood glyph’ is oddly appropriate, not only because of the amount of human suffering that Cortes’ actions and the European colonization of the Americas brought, but also because of the bloody execution of his son’s supporters, and the tragic end of his son himself, who was tortured before dying in exile in 1589.

Acknowledgements

Again, I want to thank Gabriel Kendrick Kruell for his comments on the idea of this note. All opinions presented here are mine alone.

References

Barlow, Robert. 1990. Algunas consideraciones sobre el término “Imperio Azteca”. In Obras de Robert Barlow, eds. Jesús Monjarás-Ruiz, Elena Limón, María de la Cruz Paillés. 213-220. México: INAH/UDLA

Diel, Lori Boornazian. 2018. The Codex Mexicanus: A Guide to Life in Late Sixteenth-Century New Spain. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press.

Castañeda de la Paz, María, and Michel Oudijk. 2019. El Códice Mexicanus. México: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México.

Mengin Ernest. 1952. “Commentaire du Codex mexicanus n° 23-24 de la Bibliothèque Nationale de Paris.” Journal de la Société des Américanistes 41 (2): 387-498.

Tena, Rafael, 2017. Códice Aubin. Vol. II. Facsimile edition. Mexico: INAH.

Valle, Perla. 2006. “Glifos de cargos, títulos y oficios en códices nahuas del siglo XVI.” Desacatos 22: 109-118.