Alonso Rodrigo Zamora Corona

Abstract: The famous plan of the teoithualco or sacred courtyard in folio 269r of Sahagun’s Primeros Memoriales has been of enormous importance in conceptualizing sacred spaces in Aztec religious history and archaeology, despite the uncertainties regarding its identification. This note argues that the most famous interpretation of this diagram, that of Eduard Seler (1901), probably misidentified two buildings, namely the Colhuacan Teocalli or ‘Temple of Culhuacan’ and the Cuauhcalli or ‘House of Eagles’, a temple for warriors. This misidentification stemmed from glossing over the CUAUH, cuauh·tli, ‘eagle’ glyph next to the small temple-house with the image of Huitzilopochtli, as well as from Seler’s usage of Durán’s information regarding the location of the cuauhcalli, now superseded by archaeological data.

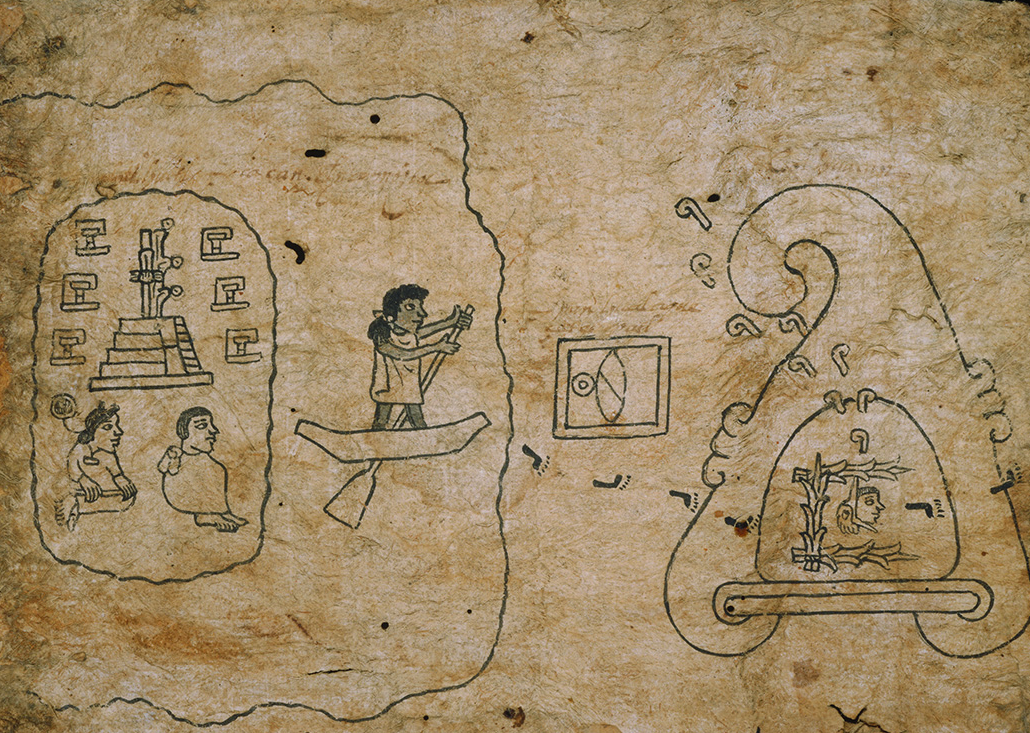

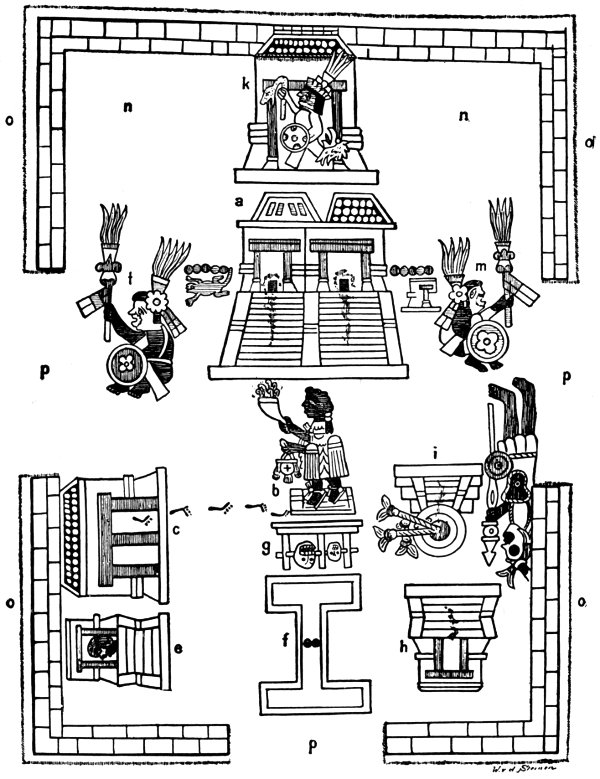

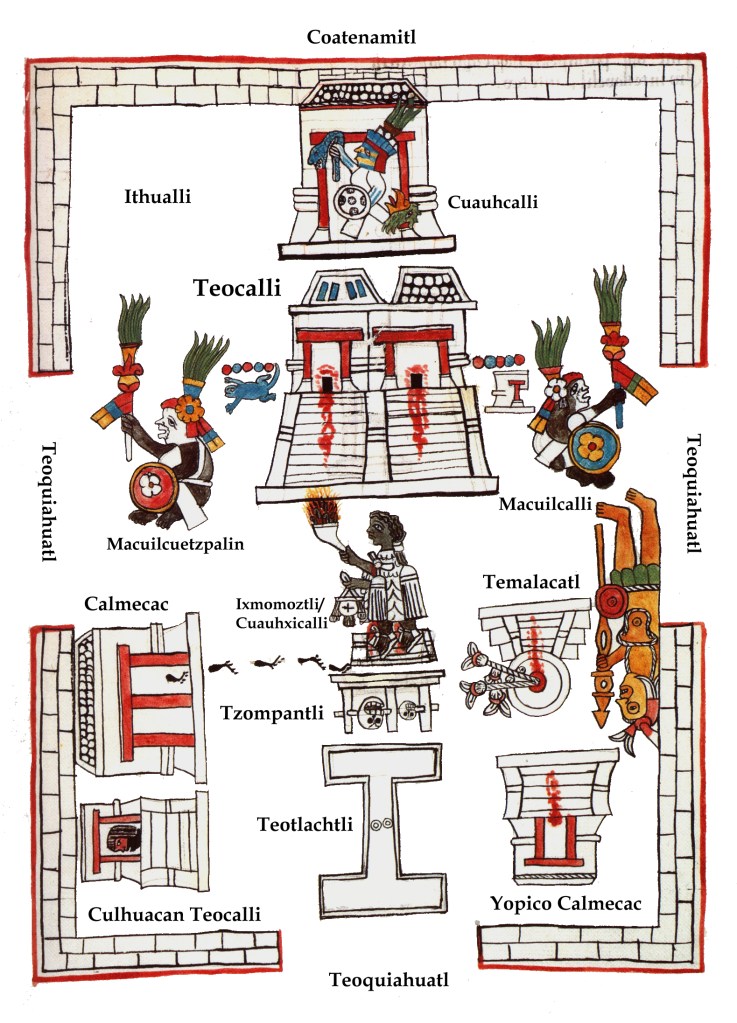

Perhaps the most famous pictography in Sahagun’s Primeros Memoriales is the representation of what this document calls cececni tlacatecolocalco, ‘many temples of the devil’, a Christian misnomer of what probably was cececni teocalco or ‘many temples of the gods’. This image, one of the few extant indigenous diagrams of a ritual compound in in XVIth century Central Mexico (others are to be found in the Plano de Papel de Maguey and arguably in Codex Borgia), is precious for its alphabetic glosses but, sadly, each of the items of the image is not correlated with certainty with its accompanying list. The first scholar to attempt this work of identification was Eduard Seler, in an article “The Excavations at the Site of the Main Temple of Mexico” (1901), dedicated to recent findings in the Historical Centre of Mexico City. Most of these identifications, which presupposed that the diagram was indeed that of Tenochtitlan’s sacred precinct, have stood firmly the test of time (Figure 1). However, there is an element, or perhaps a couple of them, which are controversial (see Sahagún 1997: 117-120), and which Seler himself considered as not as certain (nicht mit gleicher Sicherheit) as the rest: I am referring to his identification of the structure at the top of the diagram (or to the east, since indigenous maps were oriented towards that direction) with the Colhuacan Teocalli, and that at the bottom left of the diagram (North West) with the Cuauhcalli, the ‘house of eagles’, a military temple.

Figure 1. Sahagun’s plan of a sacred precinct and its identifications according to Seler (1901): a) The two great temples; b) The cuauhxicalli or ‘eagle bowl’, an altar to the sun; (c) A calmecac, priest houses; e) The Cuauhcalli or ‘house of eagles’, a temple for warriors; (f) The teotlachtli or ‘ball court of the gods’; g) Tzompantli or skull rack; h) Yopico Teocalli, the temple of Xipe Totec, the flayed god; i) The temalacatl, where the ‘gladiatorial’ sacrifice or tlahuahuanaliztli took place; k) The Colhuacan Teocalli or ‘temple of Colhuacan’, which Seler identified as a Huitzilopochtli temple; l, m) The gods 5 Lizard and 5 House respectively; n) The ithualli or courtyards; o) The coatenamitl or ‘snake wall’.

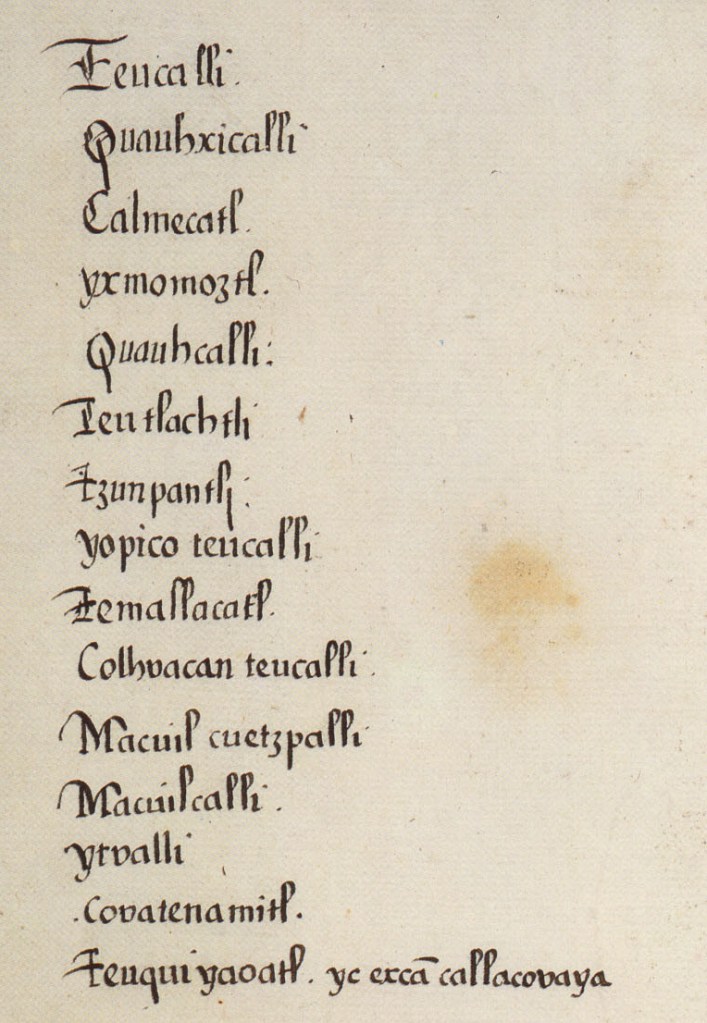

Figure 2. The original list in Primeros Memoriales: <gloss: Teucalli. / Quauhxicalli. / Calmecatl. yxmomoztl. / Quauhcalli. / Teutlachtli. / Tzunpantlj. / Yopico teucalli / Temallacatl. / Colhvacan teucalli. / Macuilcuetzpalli / Macuilcalli. / Ytvalli. / Covatenamitl. /Teuquiyaoatl. Yc excā callacovaya> Translation: “House of the gods / Eagle vesssel / Priestly school / Front platform altar / Eagle house / Sacred ball court / Skull rack / Yopico Temple / ‘Gladiatorial’ stone / Colhuacan temple / Five Lizard / Five House / Courtyard / Wall of snakes / Sacred portals, entryways in three places” (cfr. Sahagún 1997: 119-120).

Before dealing in depth with the topic of this note, namely, whether Seler’s identification of the cuauhcalli with temple e in his diagram can be still upheld, an important warning must be made. As Thelma Sullivan explains in his edition and translation of this Sahaguntine document (1997), we don’t know whether this scheme depicts either a diagram of the sacred precinct of Tenochtitlan, as many have assumed (Marquina 1960, 1964 ; González Torres 1985: 153-171 ; León-Portilla 1987a: 84-87 ; Townsend 1987: 372, 2010: 133; Matos Moctezuma 1999: 27; López Austin 2009: 32; Couvreur 2002), or an image of the sacred precinct of Tepepolco/Tepeapulco, the provincial town where Sahagun started his researches on Aztec religion, and from which the now lost pictographies that were put into text in order to create the Primeros Memoriales proceed, an opinion shared by H.B. Nicholson (cfr. Sahagún 1997: 117-120), Eloise Quiñones Queber (cfr. Sahagún 1997: 39), and Santiago de Orduña (2008). Indeed, the Primeros Memoriales stemmed from a questionnaire distributed by Sahagún among the old men of Tepepolco, in a way that has been compared (but cannot be equalled) to modern ethnology. The tlamatini or wise men in town, which did not use alphabetic writing, responded with a mixture of pictographies and logosyllabic writing, which were later re-copied and ‘translated’ into an alphabetic text, sometimes, but not always, illustrated with copies of the Tepepolcan pictographies, a work which was done by Sahagun’s Tlatelolcan students. This alphabetic ‘translation’ and redrawing is what we have today, since the non-alphabetic originals made by Tepepolcan tlacuilos, expressly recalled by Sahagun as having being in his possession many years later, are now lost (cfr. León Portilla 1999: 123-134).

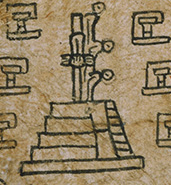

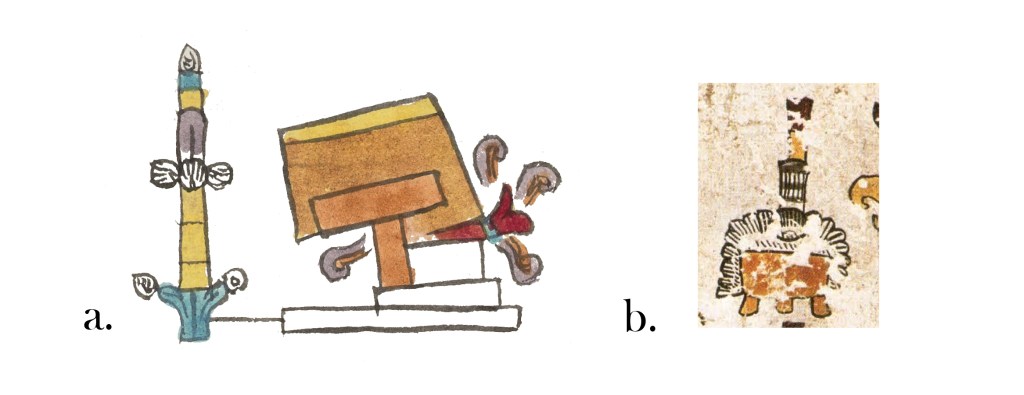

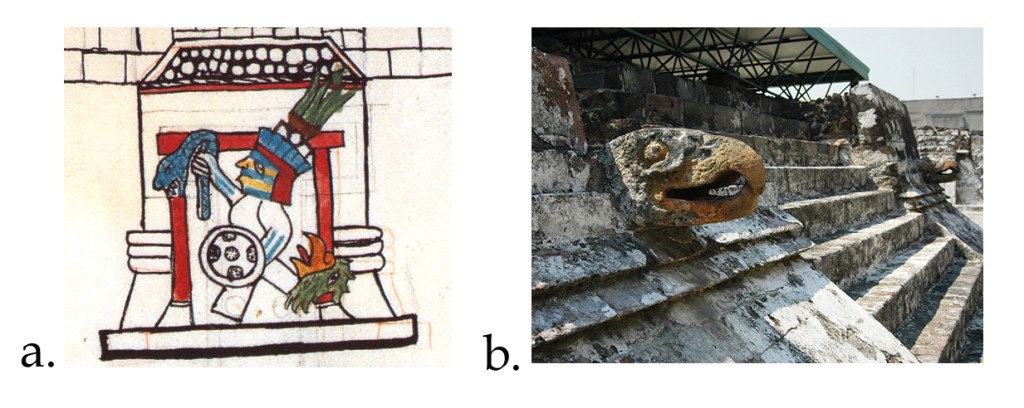

Furthermore, a third possibility exists, which Sullivan also contemplates: that this diagram was simply an idealized image of the cececni teocalco or many houses of the gods, as they were expected to exist in towns that shared (more or less) the religious cults of the Mexica-Tenochca, such as Mexico-Tlatelolco or Tetzcoco. This question is unsolvable for now, and I won’t attempt to offer any definitive solution to it. Instead, I am going to concentrate on a feature of the diagram that has been generally ignored by the commentators: the glyph CUAUH, cuauh·tli, ‘eagle’ right next to the building that Seler identified as the Colhuacan Teocalli or ‘Temple of Colhuacan’ (Figure 3).

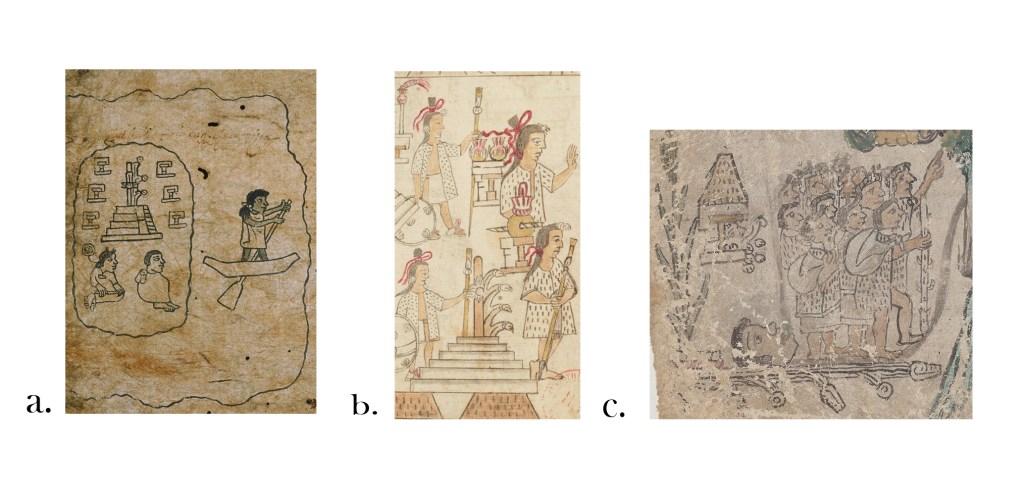

Figure 3. a) The House of Eagles in the Primeros Memoriales 269r. Notice the CUAUH or ‘eagle’ logogram in it; b) Eagle heads at the archaeological remains of the cuauhcalli, north of the main temple or huey teocalli.

From what we know nowadays about Aztec writing, this glyph is undoubtedly a logogram, and it works as a concrete label, which denotes a word beginning with the root cuauh, ‘eagle’. However, since Aztec writing was fond of abbreviations or elisions, this glyph can be correlated with two of the words of the list of the informants of Sahagun: the cuauhxicalli or ‘bowl of the eagles’, and the cuauhcalli, or ‘house of the eagles’. In fact, it could be argued that this glyph transforms the temple into a sort of logogram too, and that it must be read CUAUH-CAL, cuauhcall(i), ‘house of eagles, given the fact that, being a label rather than just an iconographic element, it can only name the temple itself, given the fact that no cuauhxicalli (a circular stone above a momoztli or altar) is in sight. Of course, this would be natural, since the real archaeological cuauhcalli had two eagle heads in its frontispice, which also must be read, as many elements in Aztec art, as a sort of label, as writing.

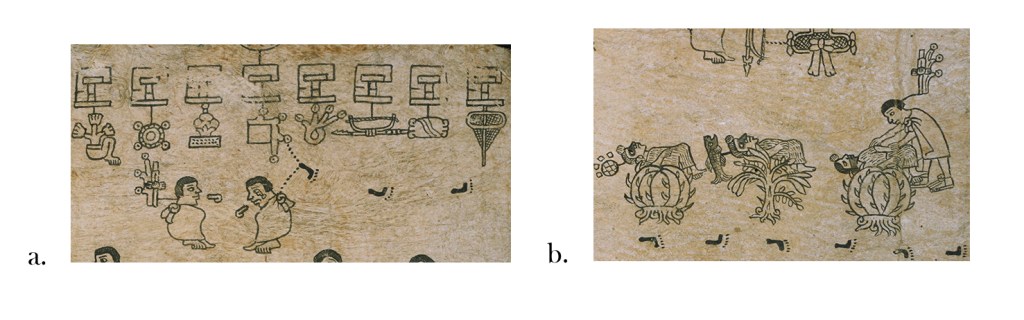

Of course, the reader would notice that, if we were to identify the cuauhcalli with the temple at the north, the label Colhuacan Teocalli would be missing its identification. Sadly, the Colhuacan Teocalli is a structure that appears nowhere in the extant information regarding Aztec culture gathered by the friars in the sixteenth century. It is missing from Sahagun’s list of the sacred buildings at the sacred precinct of Tenochtitlan, which comprised 78 edifices (Sahagun 1981: 179-193). Because of this missing information, Seler had to propose that the Colhuacan Teocalli was a temple of Huitzilopochtli represented at his original mountain abode at Colhuacan, as depicted in the first page of Codex Boturini, from which the Aztec departed in the year 1 Flint according to Codex Aubin (Tena 2017: 34). However, the main problem is that, as stated, the glyph CUAUH associated to this depiction must be necessarily assigned to some place in the list: where that to be the case, then the cuauhxicalli would have been associated with this purposed temple, something that contradicts all extant information regarding these structures, given that the cuauhxicalli was located in a separate courtyard, in a building called cuauhxicalco, next to the temalacatl (cfr. Durán 2002: 106; Sahagún 1981: 48) which is now hypothesized to have been located in front of the huey teocalli (López Luján and Barrera Rodríguez 2011).

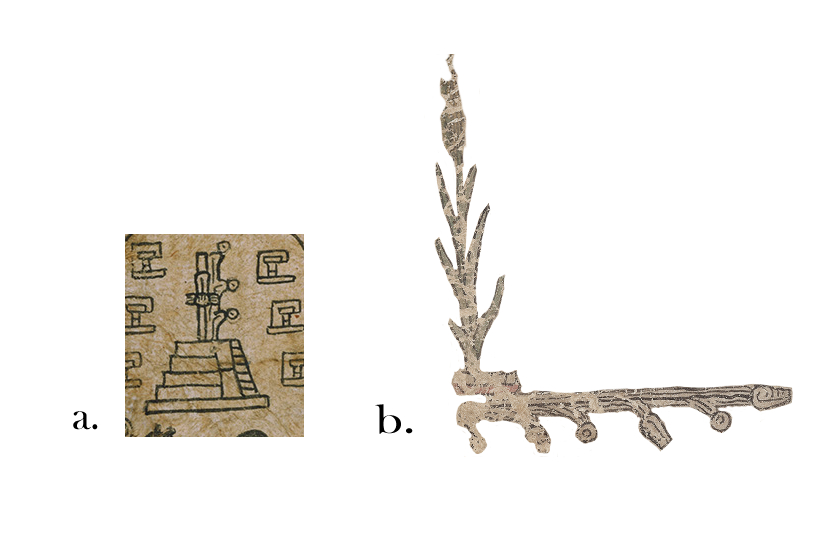

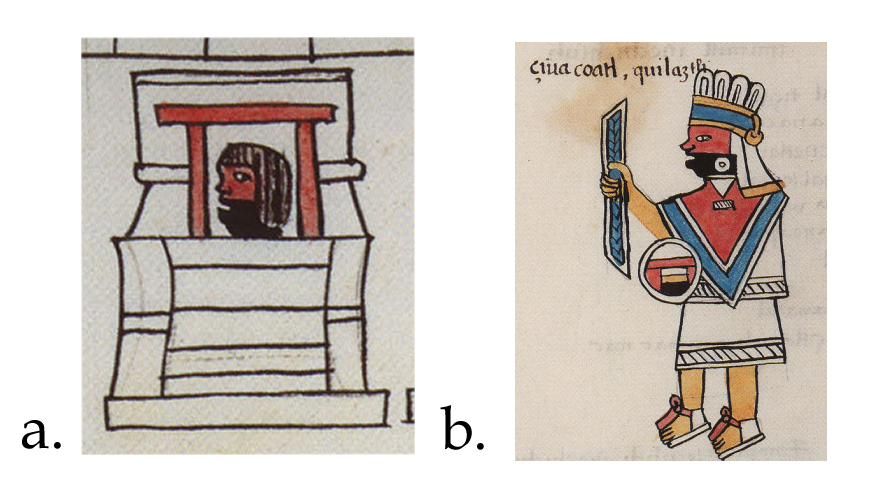

If we reject the identification of k in Seler’s scheme with the Colhuacan Teocalli, then the only other place where this temple was would be what he considered as the cuauhcalli, or e in his diagram (Figure 1). This structure, as Sullivan indicates, is clearly a temple for Cihuacoatl, the warrior goddess, called inantzi teteo or ‘mother of the gods’ in the Primeros Memoriales (Sahagún 1997: 123), identified by her facial painting, half red, half black (cfr. Sahagún 1997: 105). In the hymn dedicated to this goddess, also in the same manuscript, she is called colhoa, ‘she of Colhuacan’, as well as imaza Colhuacan, ‘the deer of Colhuacan’ (Sahagún 1997: 144). It is therefore possible to sustain the idea that the Colhuacan Teocalco was a temple for this goddess, rather than a representation of the cave of Quinehuayan in Colhuacan, the Urheimat of Huitzilopochtli, as Seler considered (1904: 778). Of course, we don’t have more evidence to make us decide for either identification, but the fact is that the CUAUH label cannot be ignored, and the idea that harmonizes more with the sources and the archaeological data available is that it is none other than the cuauhcalli, for the other possibility, that the glyph stands for a cuauhxicalli which would be in front or inside of the Colhuacan Teocalco, cannot be sustained through the sources.

As mentioned, another element of criticism against Seler’s identification is to be found in archaeology. In his article, Seler identified the Cihuacoatl temple with the Cuauhcalli, based on Duran, who asserted that the Cuauhcalli was under the place of the current Cathedral of Mexico, and stated that this was the approximate location in the diagram (to the West). However, nowadays we know that the Cuauhcalli or ‘house of eagles’ was located to the north of the huey teocalli or great double pyramid of Huitzilopochtli and Tlaloc, and right next to it (Figure 4). Thus, the archaeological sustain for Seler’s identification of the Cuauhcalli has weakened; instead, now we know that the Cuauhcalli was very near the ‘double pyramid’, probably because of its warrior connotations.

Finally, it seems redundant that Huitzilopochtli had another shrine representing his original abode at the cave of Quinehuayan in Colhuacan, for that was presumably one of the symbolisms of the great temple itself. This idea is not new: for example, Santiago de Orduña calls into question Seler’s identification, and considers that the temple that we see at the top of the diagram is an artistic reduplication of the temple of Huitzilopochtli atop the Huey Teocalli (2008: 57-59). I think that the patronage of Cihuacoatl was probably the association that Sahagun’s informants had in mind; furthermore, the term Colhuacan Teocalli was presumably a mere synonym for the temple of the goddess next to the Tlillan Calmecac, the ‘cloisters’ where the priestesses of Cihuacoatl lived, both of which were located inside the sacred precinct of Tenochtitlan (Mazzetto 2014: 148).

Figure 4. The Colhuacan Teocalli, or temple of Cihuacoatl in the Primeros Memoriales 269r.

Before proceeding to propose this small correction for Seler’s diagram, it is necessary to address the question of whether this pictography actually depicts Tepepolco rather than Tenochtitlan or an idealized version of it. In her article on the illustrations of each of the veintenas in the Primeros Memoriales, Katarzyna Granicka (2015) concluded that they could not possibly depict the provincial life of Tepepolco in account of their complexity and their lack of accordance with the glosses (2015: 224). Instead, she believes that they closely follow the celebrations at Tenochtitlan as described in the Florentine Codex and in Durán, “an important argument in favour of the hypothesis that they (the images at the Primeros Memoriales) derive from Tenochtitlan” (2015: 225). This can also be inferred from the text constantly referring to the political life of the capital, as it is the case with the chapter on rulership, which in its Chapter III deals with the general notions of the Tenochca empire rather than with the provintial life of Tepepolco. This means that, probably, the originals drawn at Tepepolco, which are lost, were re-drawn and glossed by the Tlatelolca in their own way. But the problem remains: if the Primeros Memoriales depict life in Tenochtitlan rather than in Tepepolco, what to make of this diagram, which conflicts in many points with archaeology? [1] The only solution is that which Granicka proposes, namely, that the original testimonies and pictographies gathered at Tepepolco referred to Tenochtitlan but only in an approximate fashion, being prone to mistakes and errors.

In any case, here I present my own proposal, which differs from Seler in two points only. As for the location of the cuauhxicalli or ‘vase of the eagles’, which is not apparent in the diagram, I would agree with him that in the diagram it is confused with the ixmomoztli or ‘frontal altar’. This can be sustained with the fact that all sources agree that the cuauhxicalli was in front of the Huey Teocalli and next to the temalacatl, which in turn was in front of the Yopico Teocalli, and which were part of a courtyard dedicated to war deities (Xipe and Tonatiuh, the sun). Finally, the odd location of the Cuauhcalli in the diagram, which is to the east or behind the Huey Teocalli, rather than to the north or right next to it (as it really was), could be explained by the relative lack of familiarity of the Tepepolcan tlacuilos with Tenochtitlan, as well as the fact that the actual place of the cuauhcalli is occupied in the pictography by the oversized statue of the god Macuilcuetzpalin. Of course, however, the other two possibilities mentioned above, namely, that the diagram is either of Tepepolco or an idealized illustration, are not to be discarded: however, this proposal doesn’t conflict with either. In any case, here would be the corrected scheme (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Cececni teocalco, ‘The many houses of the gods’, as depicted in the Sahagun’s Primeros Memoriales, 269r.

- Teocalli: ‘Temple’, a pyramid with two joined temples at its top, those of Huitzilopochtli and Tlaloc, also known as huey teocalli.

- Cuauhxicalli: ‘Vase of the Eagle’, a circular, sacrificial stone vessel depicted nowhere in the diagram, but which rested atop a momoztli or platform-altar next to the Temalacatl and in front of the huey teocalli.

- Calmecac: A priestly school. We can see the steps of a priest which exists from it and censes the cuauhxicalli atop the ixmomoztli or ‘frontal altar’.

- Ixmomoztli: ‘Front altar’, placed right before the great temple. Atop it lied the cuauhxicalli or vase of the eagle, a sacrificial vessel.

- Cuauhcalli: ‘House of the eagles’, a temple associated with war, denoted by the glyph of an eagles’ head, with an image of Huitzilopochtli, god of warriors. The word could also denote the war council inside the palace of Moctezuma, and any kind of barracks or war-huts. In real life it stood next to the huey teocalli.

- Teotlachtli: A ball court dedicated to the gods.

- Tzompantli: ‘Skull banner’, a rack with skulls impaled across wooden beams. Now, thanks to archaeology, we know that its edges were placed circular ‘towers’ of skulls.

- Yopico Teocalli: The temple of Xipe Totec, ‘our lord the flayed one’, god of goldsmiths, vegetation, and warriors.

- Temalacatl: A circular stone to be used in the combat between captives and warriors at Tlacaxipehualiztli, ‘flaying of men’, one of the rituals of the 18 months in the Aztec year solar year or Xihuitl.

- Colhuacan Teocalli: A temple dedicated to Cihuacoatl, warrior goddess of Colhuacan, considered, among other goddesses, as “mother of the gods”.

- Macuilcalli: ‘Five House’, a calendrical name, the temple of a Macuiltonaleque-like deity, where the execution of spies took place.

- Macuilcuetzpalin: ‘Five Lizard’, a calendrical name, the temple of a Macuiltonaleque-like deity associated with pleasure and excess. Of unknown function, although, given that other temples dedicated to the Macuiltonaleque were associated with the execution of captives, it could have had a similar purpose.

- Ithualli: ‘Courtyard’, the patio itself. In the Florentine Codex (II: 179), the informants call the whole of the sacred precinct in ithual catca Huitzilopochtli, ‘The courtyard where Huitzilopochtli was”. It is possible that the term, ‘courtyard of the god’, was a synonym for these precincts as a whole, rather than just of the dancing plazas in them (cfr. Wood 2020, entry ‘Teuitoalco’).

- Coatenamitl: ‘Wall of snakes’, the surrounding wall of the precinct, perhaps decorated with snakes. Not to be confused with the Coatepantli, an enclosure of snakes around the huey teocalli itself.

- Teoquiahuatl: ‘Sacred portals’; as the Primeros Memoriales explain, there were three of them, on all sides except on the rear of the great temple.

Acknowledgements

I want to thank Stan Declerc and Gabriel Kruell for their commentaries and suggestions while reading this entry; all the faults in this text are mine alone.

References

Couvreur, Aurélie. 2002. “La description du Grand Temple de Mexico par Bernardino de Sahagún (Codex de Florence, annexe du Livre II).” Journal de la Société des américanistes 88: 9-46.

Durán, Diego. 2002. Historia de las Indias de Nueva España e Islas de Tierra Firme. México: CONACULTA.

González Torres, Yolotl. 1985. El sacrificio humano entre los Mexicas. Mexico: INAH/FCE.

León-Portilla, Miguel. 1987a. ‘The Ethnohistorical Record for the Huey Teocalli of Tenochtitlan.’ In E. H. Boone, ed. The Aztec Templo Mayor, 71-95. Washington DC: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection.

Granicka, Katarzyna. 2016. “En torno al origen de las imágenes de la sección de las veintenas en los Primeros Memoriales de fray Bernardino de Sahagún.” Revista Española De Antropología Americana 45 (1), 211-227.

López Austin, Alfredo. 2009. Monte Sagrado-Templo Mayor. El cerro y la pirámide en la tradición religiosa mesoamericana. Mexico: INAH, UNAM/IIA.

López Luján, Leonardo, and Raúl Barrera. 2011. “Hallazgo de un edificio circular al pie del Templo

Mayor de Tenochtitlan.” Arqueología Mexicana 112: 17.

Marquina, Ignacio. 1960. El Templo Mayor de México, INAH, Mexico.

Matos Moctezuma, Eduardo. 1999. “Sahagún y el recinto ceremonial de Tenochtitlan”, Arqueología Mexicana 6 (36): 22-31.

Mazzetto, Elena. 2014. Lieux de culte et parcours cérémoniels dans les fêtes des vingtaines à Mexico – Tenochtitlan. Oxford: Archaeopress.

Orduña, Santiago. 2008. Coatepec: The Great Temple of the Aztecs. Recreating a Metaphorical State of Dwelling. PhD Thesis, School of Architecture. McGill University.

Sahagún, Bernardino de. 1997. Primeros Memoriales, T. D. Sullivan (trad.), University of Oklahoma Press, Norman.

Sahagún, Bernardino de. 1981. Florentine Codex: General History of the Things of New Spain. Book 2: The Ceremonies. Trans. C. E. Dibble and J. O. Anderson. Santa Fe, NM: The School of American Research.

Seler, Eduard. 1904. “Die Ausgraben am Orte des Haupttempels in México”. In Gesammelte Abhandlungen zur Amerikanischen Sprach- und Alterthumskunde. Second volume, 767-912. Berlin: Asher & Co.

Townsend Richard, F. 1987. “Coronation at Tenochtitlan.” In The Aztec Templo Mayor, ed. E. H. Boone, 371-409. Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, Washington D.C.

[1] For example, by locating the cuauhcalli either behind the Huey Teocalli, or in front of it.