Abstract: In 2018, Lori Boornazian Diel identified and analysed a Nahuatl hieroglyphic version of the Catholic Articles of Faith in Codex Mexicanus 52-54. This entry proposes a detailed re-analysis of this sequence, which is unique in the corpus of Aztec writing in the sense that it transcribes full sentences in a purely logosyllabic fashion, and could even contain an exceptional native phonetic sign working in a similar way to those of our alphabet. In any case, these glyphs shed an unusual light in the richness and variety of scribal procedures used in Aztec writing.

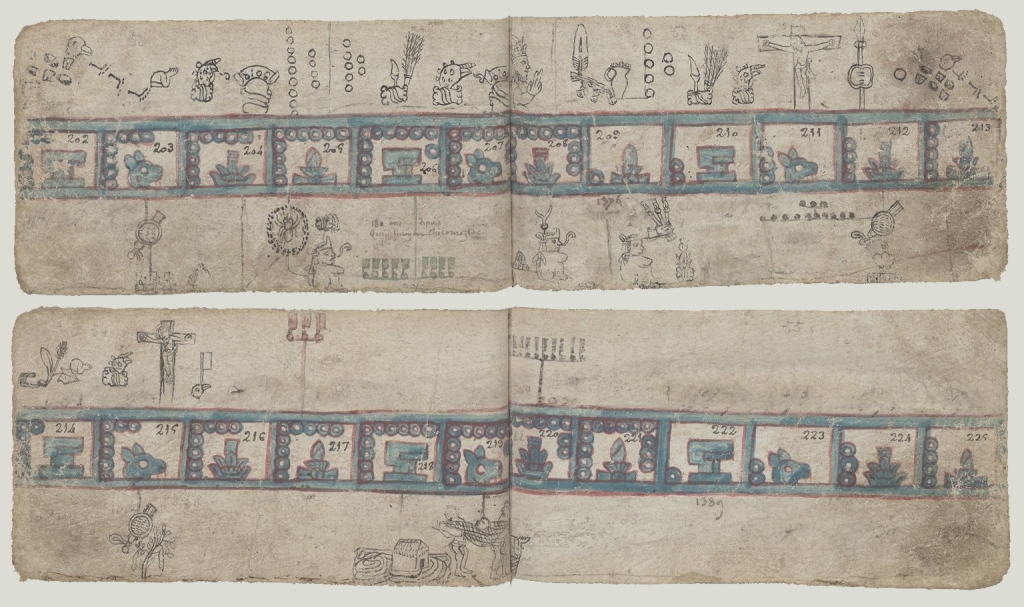

A compendium of calendrical, historical, medical and religious texts produced during the XVIIth century, the Codex Mexicanus is a formidable monument to the survival and acculturation of Aztec writing in the second century of colonial domination. Its pages still hide many mysteries, but the majority of them have been successively solved by the work of scholars such as Ernest Mengin (1952), Lori Boornazian Diel (2018), as well as María Castañeda de la Paz and Michel Oudijk (2019), in their respective in-depth analyses and editions. One of such mysteries was until recently, the identification of a section in pages 52-54 which seemed to depict a Christian text (Figure 1). It was only fairly recently that this section was identified as being a Nahuatl hieroglyphic version of the Articles of Faith, a notable insight which was the result of the collaboration between Diel, Elizabeth Boone and Louise Burkhart (Diel 2018: 176).

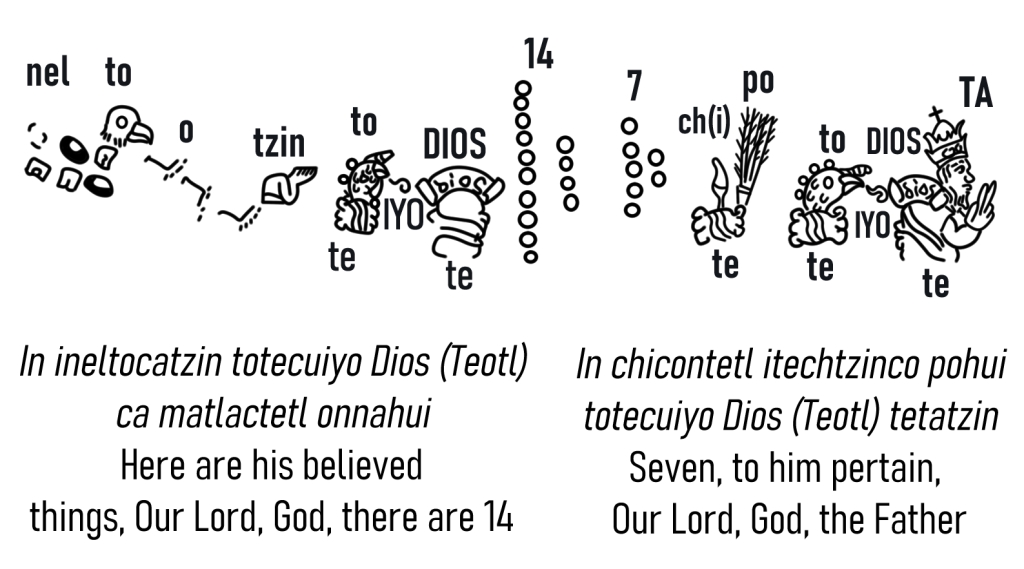

However, despite the fact that this identification is to be considered as certain without any reservations, a new analysis of each of the signs in this pictorial segment can still yield some surprises. Certainly, this work has been started by Diel, who in her own analysis (2018: 167-169) proposed convincing readings for most of these signs, and it has been partially continued by Gordon Whittaker in his recent book on Aztec writing (2021: 92). However, some finer details and surprising new signs can still be obtained when working from the recent advances brought in our understanding of Nahuatl writing (Lacadena 2008, Whittaker 2021). In general, these glyphs seem to confirm Whittaker’s assertions that a more flexible way to conceptualise the often productive and surprising scribal resources of Aztec writing is needed. First, I will present the reader with each of the halves of this new proposed analysis (Figures 2 and 3), and then, I will comment on the readings that were not already figured out in previous works in detail.

Commentary

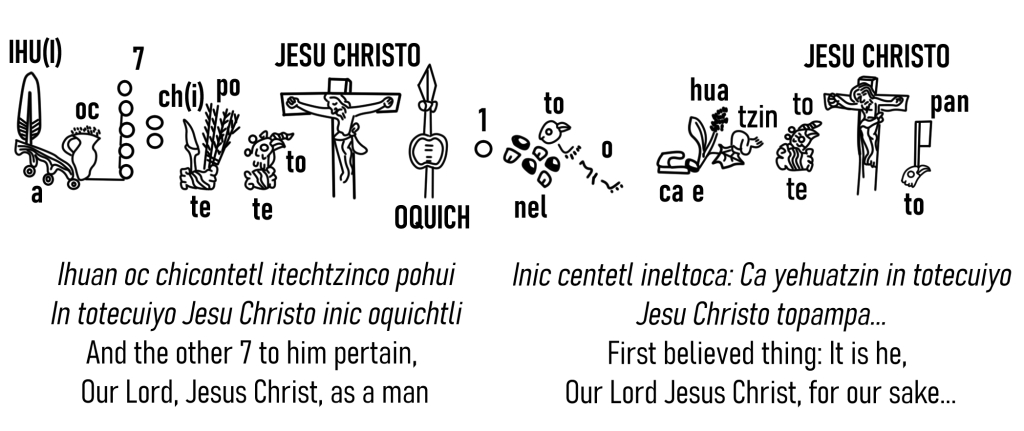

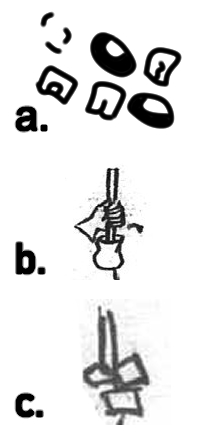

nel: The iconography of this hapax glyph (cfr. Davletshin 2021: 80) depicts some beans and maize kernels mixed together. Diel read it as cin-e and considered a phonetic approximation to inel (2018: 148). The actual reading of the sign comes from the root NELOA, “to get mixed, to stir up something, to make a mess of something” (Karttunen 1992: 164). The word suffers here a strongly irregular acrophonic process and yields, without any regard to the syllabic structure of the word of origin, the irregular syllabogram nel. This sign will reappear later in the prayer, where its occurrence right after a sign reading 1, ce, ‘one’ discards any possibility of the maize kernel being the syllabogram ce. A more common variant of this sign (b), depicting a beater (aneloloni) exists in Matrícula de Huexotzinco 623r, where a stirring tool gives the name oc-nel, Aocnel; in other version in folio 560v (c), the beater complements the logogram XIUH to read XIUH-nel, Xiuhnel (Thouvenot 2012).

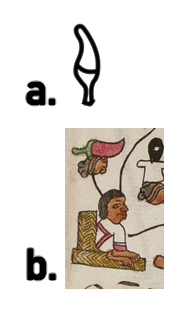

IYO: Identified by Diel as cuica, ‘to sing’, this breath scroll could stand for the unattested root IYO-TL, hypothesized by Karttunen to be implied by the better-known form IHIYO-TL, ‘breath, respiration’, itself a product of reduplication (1992: 98). It forms the final section of the word totecuiyo, ‘our lord’, a title that was both applied to the Christian god as well as to Tezcatlipoca in poetic texts such as Romances de los Señores de la Nueva España (Bierhorst 2009: 7)

DIOS-te: The banner saying the Spanish word Dios was taken into account in Diel’s analysis, but the stone (tetl) glyph was considered a mere marker with no phonetic value (2018: 168). This is actually a bilingual glyph, a phenomenon that can be found in Codex Cuaxicala, also known as Codex Xicotepec (Stresser-Pean 1995: 85). It states the word God in two languages: Spanish (Dios), and Nahuatl (Teotl).

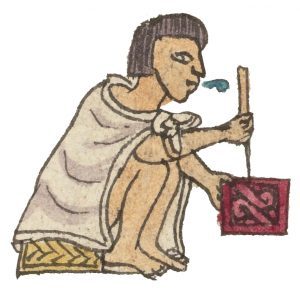

ch(i): The syllabogram chi, not recognized in the current version of the syllabic grid (Davletshin 2021: 48), actually appears in Codex Telleriano Remensis, where it forms part of the name te-chi, (Mo)te(l)chi(uhtzin), Motelchiuhtzin (b). However, in this case, the vowel is not read. This extreme acrophony cannot be equated to synharmony in Maya writing, given the fact that this phenomenon only happens at the end of a word (Johnson 2013: 62). Thus, the most probably possibility is that this sign denotes the phoneme /č/ being thus perhaps the only case of a true Aztec “alphabetic” sort of sign (!), although no doubt inspired by the contact with Western writing.

IHU(I)-a: Another ‘aberrant’ reading obtained by an irregular acrophonic process cutting right through the logogram IHUI without any regard for syllabic structure, in order to obtain, plus the syllabogram a, an incomplete spelling of the word ihuan, ‘and’.

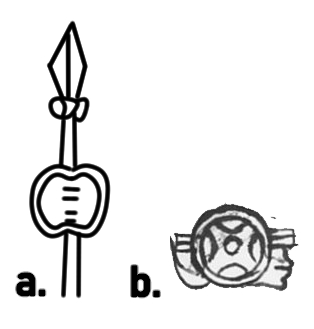

OQUICH: Interpreted by Diel as referring to the human nature of Christ by alluding to his death (169), a variant of this logogram for oquichtli, ‘man’ is attested in Codex Huexotzinco 689r, where the shield is a native chimalli and some darts (b) rather than a Spanish adarga and lance (cfr. Thouvenot 2012). Hence, the shield and spear denote manliness, which belongs to the actual semantics of the word, which “when combined can refer to masculinity, manliness, courage, bravery; might also refer to the son of God (see Molina and attestations)” (Wood 2020).

Closing remarks

Filled with unusual readings and signs, this Catholic prayer in Aztec hieroglyphs must, of course, be taken as a unique case, rather than as representative of the whole system of Nahuatl writing. We can also ponder upon the fact that Christian prayers are canonical and fixed texts which do not admit any variation on their recording, hence the use of a purely logosyllabic system here, totally unusual. However, despite these irregularities, this text is truly native, hence the astounding innovations present in it within the indigenous tradition, which are in many cases difficult to understand for us: in contrast, the ‘Testerian’ writing, with its newly forged signs and its dominant pictographic nature (cfr. Galarza 1992), was more or less a rupture with past modes of representation.

However, despite being quaint, and despite its exceptional character, this text is not at all inconceivable within what has been suspected from Aztec writing in recent years. Thus, in his latest book on Aztec writing, Gordon Whittaker has urged us to consider the enormous array of possibilities that this system had at its disposal for denoting syllables and words (2021), which perhaps make a fixed syllabic grid, such as that present in Maya writing, somewhat deceiving or at least not telling the whole story. Instead, I suggest that, if we are to move beyond the reading of proper names in Aztec codices, scholars must embrace the creativity and originality of the tlacuilos in their writing endeavours, which, as we have seen, could even yield, just in this case at least, a true letter obtained by a complete acrophonic process, similar to those which gave rise to our own alphabet.

References

Bierhorst, John. 2009. Ballads of the Lords of New Spain. The Codex Romances de los Señores de la Nueva España. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press.

Castañeda de la Paz, María, and Michel Oudijk. 2019. El Códice Mexicanus. México: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México.

Davletshin, Alberto. 2021. “Descripción funcional de la escritura jeroglífica náhuatl y una lista de términos técnicos para el análisis de sus deletreos” Estudios de Cultura Náhuatl 62: 43-91.

Diel, Lori Boornazian. 2018. The Codex Mexicanus: A Guide to Life in Late Sixteenth-Century New Spain. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press.

Galarza, Joaquín. 1992. Codices Testerianos. Catecismos Indigenas. El Pater Noster. Mexico: Tava.

Mengin Ernest. 1952. “Commentaire du Codex mexicanus n° 23-24 de la Bibliothèque Nationale de Paris.” Journal de la Société des Américanistes 41 (2): 387-498.

Karttunen, Frances. 1982. An Analytical Dictionary of Nahuatl. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press.

Lacadena, Alfonso. 2008. “Regional Scribal Traditions: Methodological Implications for the Decipherment of Nahuatl Writing”. The PARI Journal, 8, 4, pp. 1-22.

Stresser-Pean, Guy. 1995. Códice de Xicotepec. Mexico: Fondo de Cultura Económica.

Thouvenot, Marc. 2012. Tlachia [online]. Editions sur Supports Informatiques <https://cen.sup-infor.com/#/home/tlachia>

Whittaker, Gordon. 2021. Deciphering Aztec Hieroglyphs: A Guide to Nahuatl Writing. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Wood, Stephanie. 2020. “Oquichtli” [online]. Online Nahuatl Dictionary <https://nahuatl.uoregon.edu/content/oquichtli>

muy interesante!

LikeLiked by 1 person

[…] in the spelling of the name Motelchiuhtzin in Codex Telleriano-Remensis 43r, discussed in another post of this blog, were not anomalous but possibly conventional. Besides logosyllabic spellings, the […]

LikeLike

[…] in the spelling of the name Motelchiuhtzin in Codex Telleriano-Remensis 43r, discussed in another post of this blog, were not anomalous but possibly conventional. Besides logosyllabic spellings, the […]

LikeLike